“The Columbia River typically united rather than divided human populations.”

“Realize the power of the river– against the backdrop of the hills– feel the significance of the place through its geography: a confluence of economy, living culture, subsistence, business and ceremonies. Look closer to understand better the confluence of the great Columbia River with the Snake River supporting activities, towns and people– to help people live. We are one with it.” -Antone Minthorn.

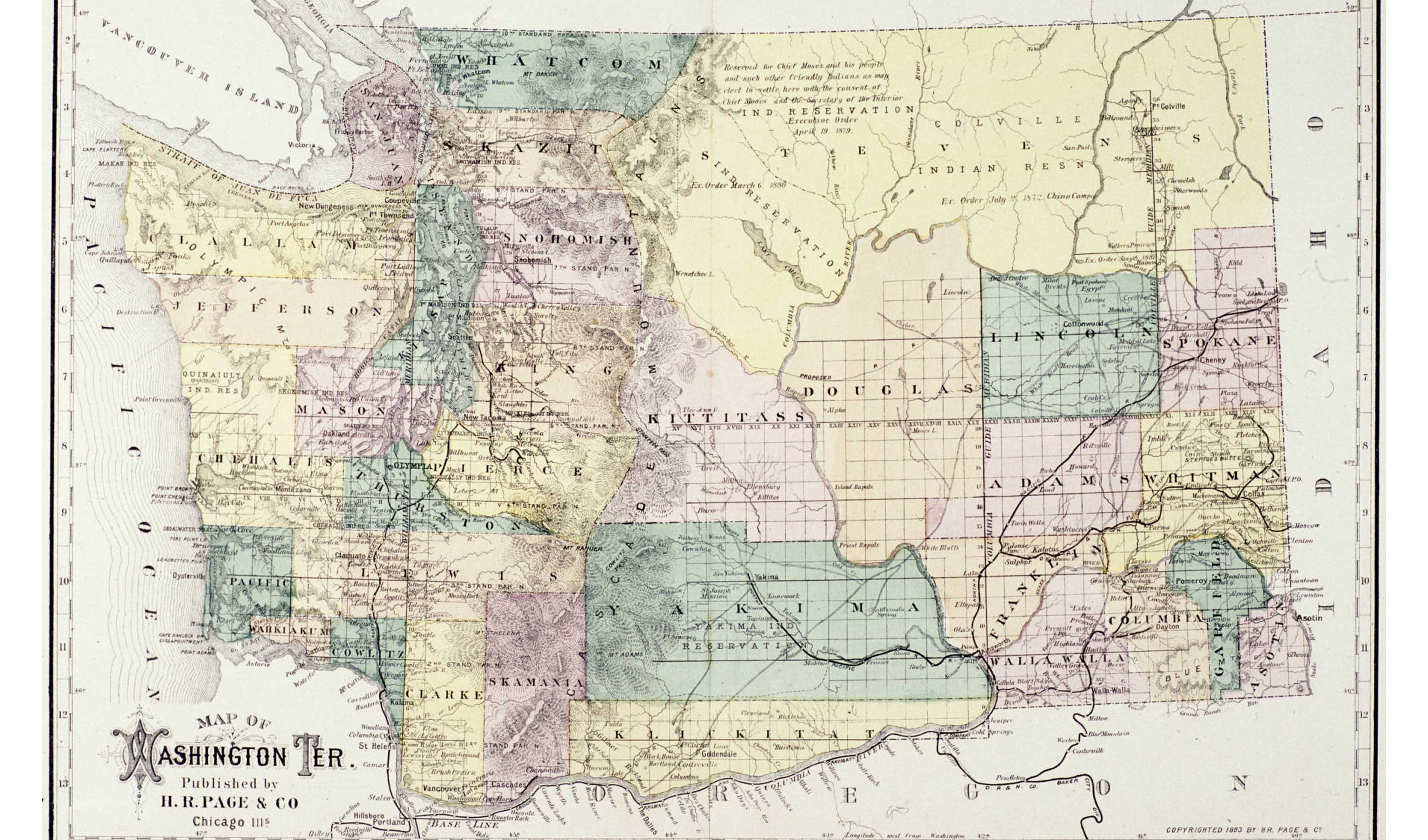

Unlike contemporary or Euro-American geographic borders or international treaties designating regions for which rivers serve as natural dividing lines between states or nations, “the Columbia River typically united rather than divided human populations.”[1] Following the rhythm of the seasons, the Columbia was the table at which to eat together and then to move on.

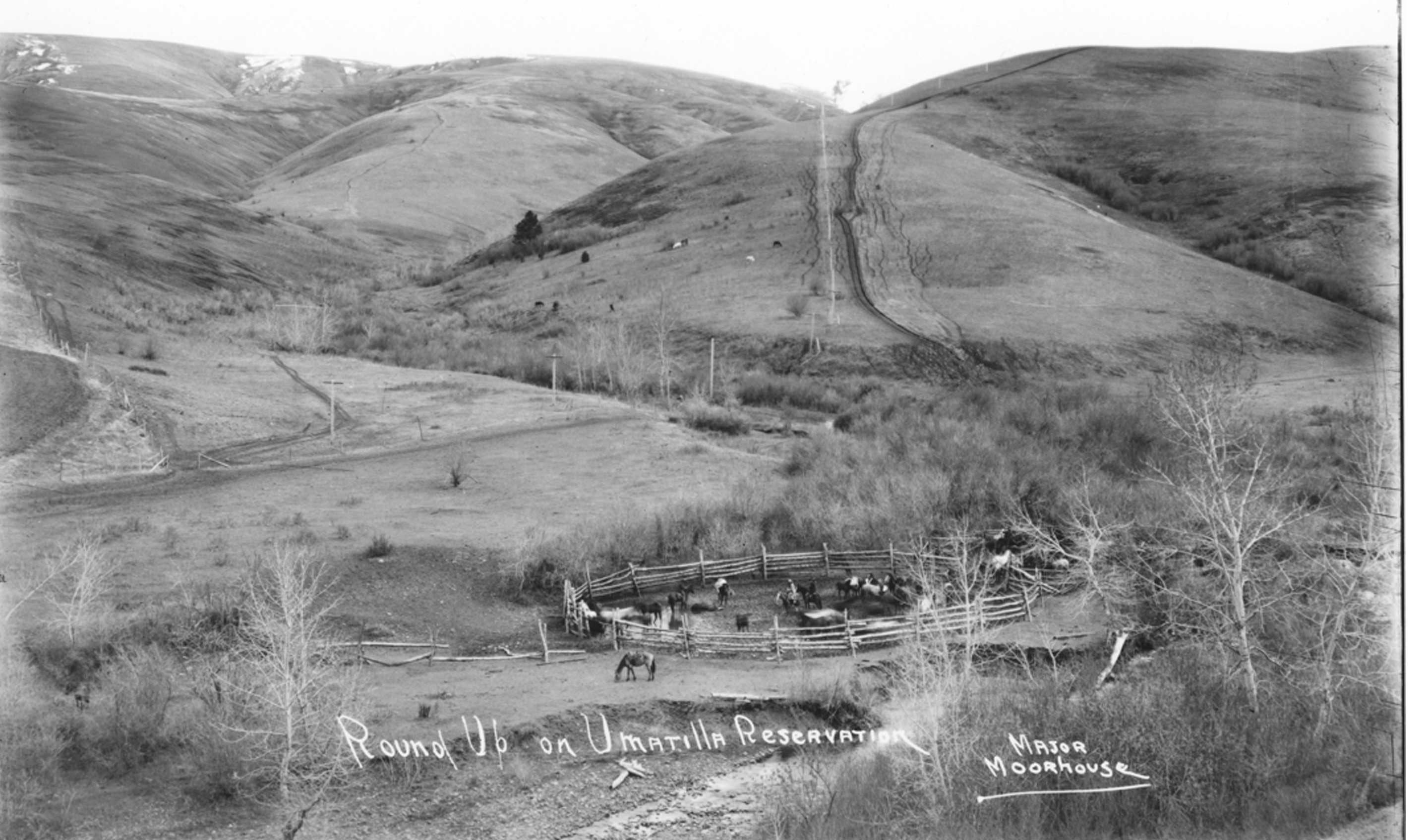

Nourishment for all people comes from the land and the rivers but the imbalances introduced by clashes of cultures and human priorities create challenges to its sustainability for ecology, environment and cultural development. By the mid-19th century, the renowned Oregon Trail followed a major portion of the Snake River, leading American settlers westward toward expansion of farmlands, towns and cities. Steamboats and railroads moved agricultural products, minerals and building materials along the Columbia and its tributaries. River landings for cordwood fuel for the steamboats often burgeoned into settlements and towns. Most river towns faced the water because travel was easier via waterways than by constructing wagon roads across the country. The Northern Pacific created the town of Ainsworth at the site of the confluence, building saw mills and boarding houses that employed and hosted over 6000 workers in the 1880’s as they laid the tracks that would connect the Transcontinental Railroad from Montana to the Pacific. Rail beds were blasted and tributaries rerouted to accomplish the monumental task of building a railroad across thousands of miles of undeveloped land.

The powerful steep flow of the Snake has been utilized since the 1890’s to generate hydroelectricity, enhance navigation and provide irrigation water. Today the Columbia-Snake river system, including Canada, has over 400 dams for hydroelectricity and irrigation. There are 14 major dams on the Columbia and 15 major dams on the Snake River. The dams were built to meet a variety of demands including flood control, navigation, storage and delivery of stored water, reclamation of public lands, and hydroelectric power. Several dams have been proposed for removal to restore some of the rivers’ once-tremendous salmon runs.

End Notes

[1] Fisher, Andrew. Shadow Tribes. Illinois: University of Illinois Press. 2015.