Native American traditions speak to respecting nature and protecting the gifts of the earth so that they may renew and all humanity will benefit. Trade-based economies in the Northwest reinforced those philosophies – trading fish for horses, food for metal tools, and sharing winter stores with those in need. Thanksgiving was one winter holiday invoked by President Lincoln during the Civil War as a brief armistice between North and South to encourage all Americans to recall their blessings in the midst of the nation’s most tragic struggle between families, friends and citizens divided.

Since then, we’ve grown to appreciate some of the deeper meanings of Thanksgiving – a time of sharing when non-indigenous people journeyed to North American shores and suffered ill-prepared through a dire winter. With the help of the Mashpee people of the Wampanoag tribe, they learned to plant crops, build houses, and working together, the Pilgrims and the Mashpees received a bountiful harvest in autumn.[1]

Thinking of the various relationships of indigenous people to the land and the strikingly different orientation of the American emigrants to the Northwest, I came across a fascinating story in a 1921 Sunset Magazine. The article declared that the “spirit” of Seattle was “sagging” but, in this instance, the magazine writer, Walter Woehlke believed that was a positive turn toward the future. Between 1896 and 1920 – from the Alaskan Yukon Gold Rush to the closure of the shipyards after World War I, the Northwest boomed with people, prosperity and prolific production because of its abundant natural resources, but he feared those resources were overused and unrenewed. By 1920, western Washington State had become home to more than ten percent of the nation’s available “water power.”[2]

Private entrepreneurs throughout the Northwest were developing utilities and marketing hydroelectric power to communities and businesses. There were few federal regulatory guidelines and rural public utilities competed with municipal private utilities for control and pricing.[3] In the early 1920’s there were 4,000 private utilities competing with 3,000 public utilities but private ownership was better financed and influential companies pushed for the merger of over 1,000 power companies in 1926 alone.

Today, only about 200 private utilities exist with more mergers ongoing today.Between the late 1800’s and the early twentieth century, another natural resource – Northwest forests — echoed with the sound of axes felling trees and a proliferation of mills buzzed and screeched as the sawn lumber and shingles spewed out of production lines. As early as 1920, if driving the Pacific Highway between Portland, OR and Vancouver, BC – a stretch of over 400 miles — already there were no more than five miles of virgin [old growth] timber remaining.[4]

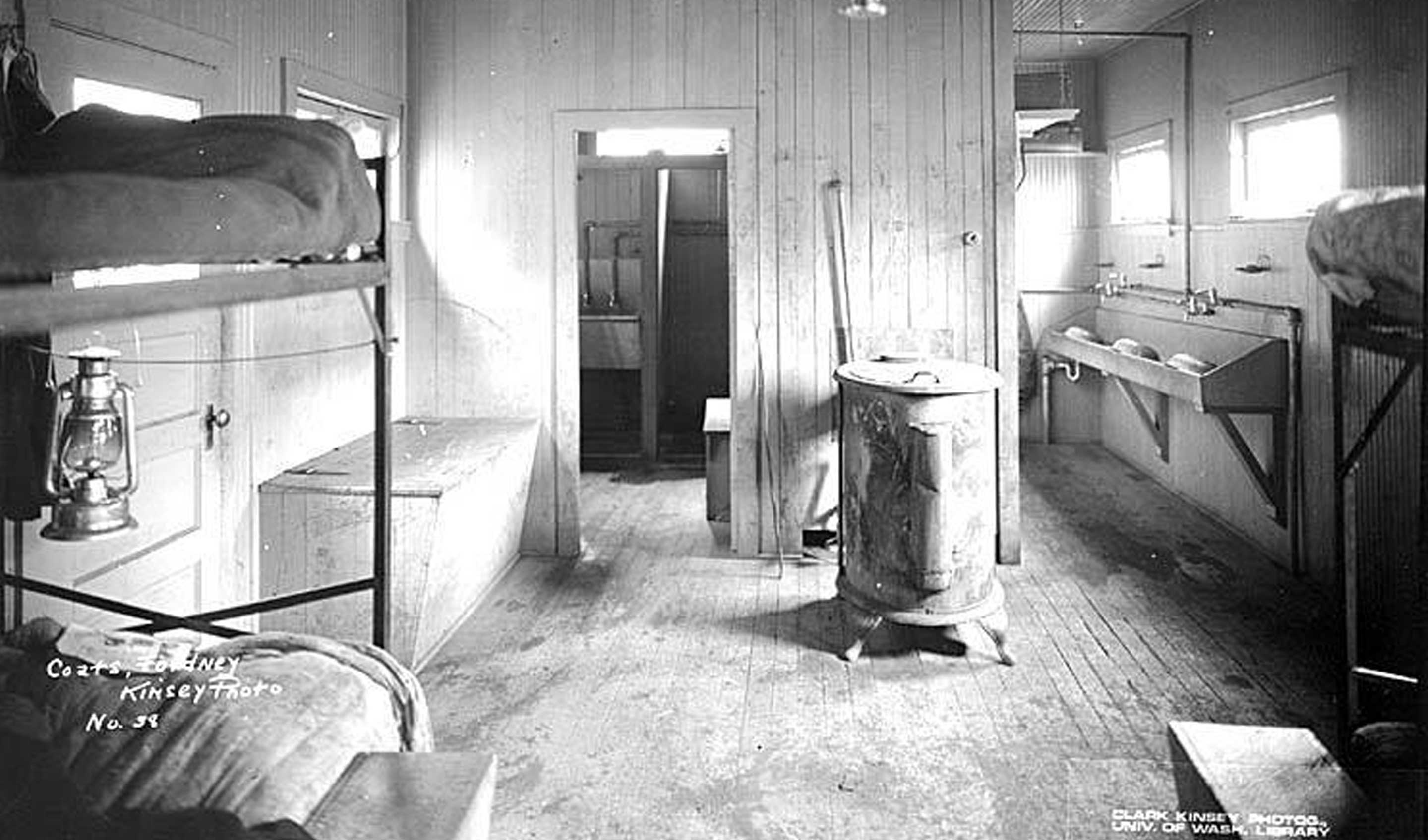

Though timber barons abounded still, building magnificent homes in Portland, Seattle, and towns in between, they might have become even richer if patience and long-term forest management had prevailed. The stunning lumber photography of the Kinsey Brothers (ca. 1890-1945) shows Douglas fir trees towering over 200 feet tall and more than 10 feet in diameter that were cut to the base, pock-mocking stately forests with useless stumps difficult to clear. There were few efforts to replant trees.

Much of the timber cut in the early twentieth century was rushed to markets so quickly and in such vast quantities that lumber prices fell at or below production and transportation costs. It was dumped into Southern competitive markets and shipped to the Midwest with diminished profits. Impatience depleted the environment and profits at an astounding rate.

At Vancouver Barracks during World War I, the world’s largest spruce cut-up mill sprang to life practically overnight to produce lumber for manufacturing French, British and Italian aircraft. Operated by Army troops at the height of production in 1918, the Vancouver mill was cutting and shipping one million board feet of Sitka spruce lumber every day.[5]

The offices occupied by Confluence today are located in what was the administrative building for the federal project. The war ended before much of the spruce lumber cut at the Barracks reached Europe and sadly, the soft lumber glutted the US market for several years at extremely low prices.[6] Throughout the Northwest, World War I created a severe housing shortage as workers poured into Washington and Oregon communities from around the nation for labor in the booming industries. This situation worsened at the end of the war as laborers were stranded without even bunkhouses once provided to the employees in logging camps.

There was “a distinct economic loss [to the region] for the sake of the small present gain,” noted Sunset writer Woehlke in 1921. He believed that with proper management and handling, “lumber could lose its extractive character and become a perpetual source of wealth.”[7] The lumber prices received contributed nothing to reforestation or to even pulling stumps and creating productive farm land in the then agriculturally-based society of the Northwest.

Those once “booming” lumber industries like sail and steam shipbuilding, housing and business construction, manufacturing, aircraft development, with off-shoots like fuel, cabinetry, railroad ties, telephone poles, and plywood production slowed to a snail’s pace. As American markets fell, the West Coast looked to export markets to fill the gap.

Meanwhile, the efforts of conservationists like Gifford Pinchot and preservationists like John Muir captured the attention of communities, businesses and the federal government. Pinchot campaigned for closely-managed lands that would become “National Forests.” Muir was a strong advocate for preserving the wonders and beauties of lands with protection from poachers, and they became “National Parks.” Both helped set the high standards those agencies strive to achieve today.Woehlke was writing in Sunset Magazine at a time when attitudes in the West were undergoing a reformation.

The population doubled, and then tripled in the decades following emigration via the Oregon Trail, in the aftermath of the Civil War, and the opening of the Transcontinental Railroad. Woehlke keenly believed that attitudes were shifting and the philosophy of “community” was evolving.[8] “The old-time spirit of the pioneer West,” he wrote, “the fighting spirit that places the interest of the individual first and resents the suggestion that the community also has an interest to be preserved … [is] the glorious spirit of daring adventure for personal profit that reclaimed the Far West from the wilderness in two generations and squandered natural wealth enough for five generations in the process.”[9]

Less than a decade after the Woehlke article appeared, the country was in the vice-grip of the Great Depression and a tanking economy worldwide. Still more land would be “reclaimed” by hydroelectric power, irrigation and industry. The youthful Civilian Conservation Corps, in conjunction with the Army and the Forest Service, concentrated on forest management, planting trees, fighting and helping to prevent forest fires, and educating and directing young men toward purposeful lives.

The Great Depression and World War II pushed the American public and private industry to reorganize collectively through labor unions and federal regulations that often marginalized individual businesses and gain, and later, helped promote renewable resource practices, albeit generally much too late.With time-honored traditions of love and respect for nature and its own rejuvenation, Native Americans were left at the sidelines only to watch in dismay. Rebuked, their teachings of honor for the innate cycles of life and the interwoven gifts of land and water were considered pointless and primitive. Now we know, they were right.