In 1881, Lieutenant C.E.S. Wood, a law student at Columbia University, was among a group of several officers who submitted essays to the Journal of the Military Service Institution of the United States. The subject was “Our Indian Question.” Brevet Generals John Gibbon and Nelson Miles submitted essays. General Gibbon won first prize; Lieutenant Wood took second place and General Miles took fourth place. Captain Edmond Butler and Lieutenant T.M Woodruff took third and fifth places respectively.

After graduation, Wood was transferred back to the Department of the Columbia. His Commanding Officer, living in what is known today as the “Howard House” on Vancouver’s Officers’ Row, was General Miles. Miles chastised Wood at for acquiring a law degree at the Army’s expense and opening a private practice. He banished Wood to Fort Stevens on the Oregon Coast, and disagreements between Wood and Miles were never resolved.

Disagreement first erupted at the end of the Nez Perce War when in Wood felt that Miles had taken all of the praise and left the disdain to General Oliver Otis Howard “unjustly.” Wood resigned his commission to Miles at Vancouver Barracks in 1883, and opened a full-time law practice in Portland, the first and oldest law firm in Oregon. In 1885, just prior to completion of the Commander’s mansion on Officers’ Row (today known as Marshall House), Wood’s uncle by marriage, General Gibbon, became the Commander of the Department of the Columbia.

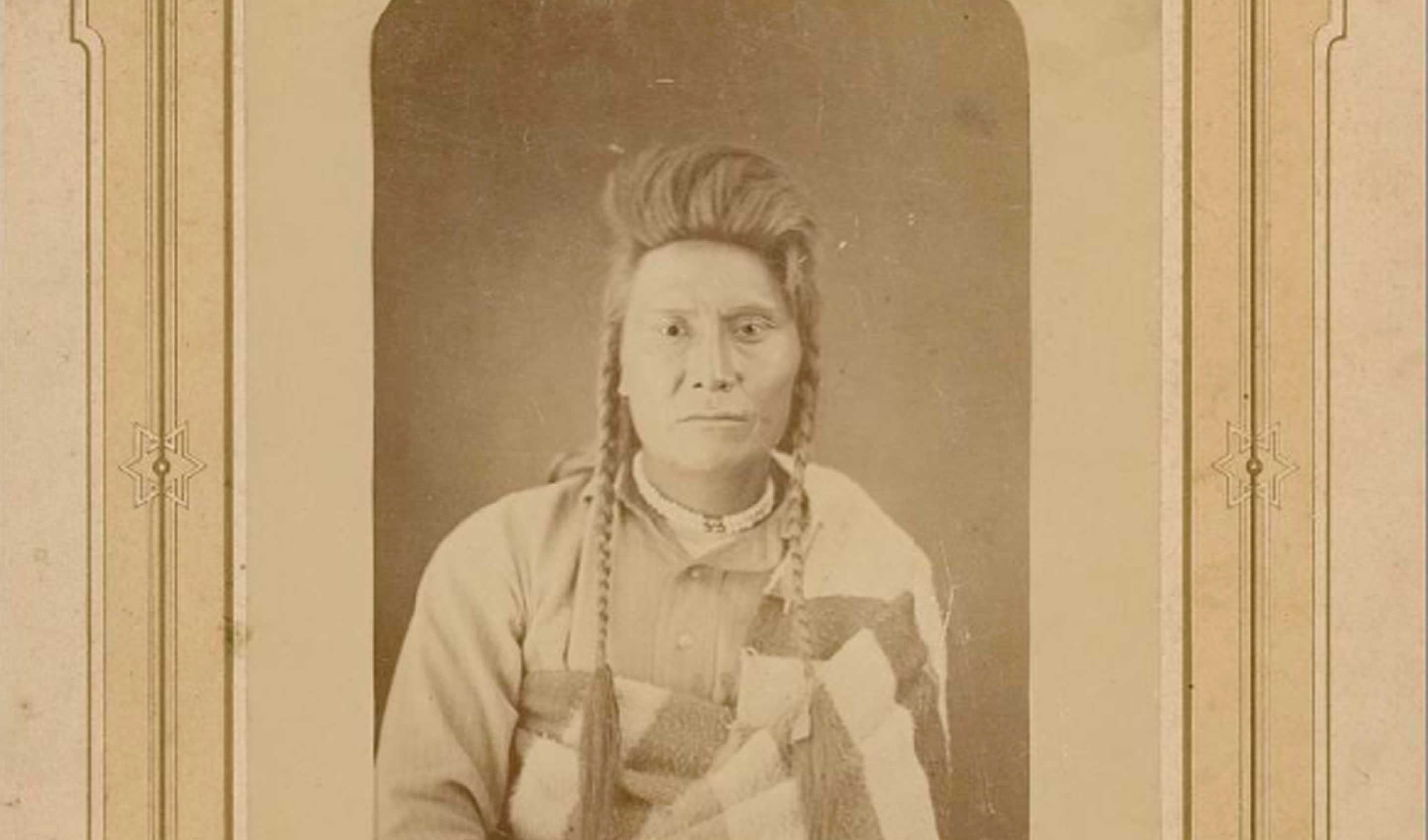

Wood is credited with recording Chief Joseph’s surrender speech at Bear Paw Mountain and releasing it to the press that autumn of 1877. As General Howard’s aide, Wood and Howard were the only two soldiers to follow the entire 1,170 mile trail of the Nez Perce. Wood and Chief Joseph became strong friends after the war, and Howard, Miles, and Wood were responsible for introducing Chief Joseph to Congress and helping to secure the band’s return to the Northwest. For two autumns in 1893 and 1894, Wood’s teenage son Erskine accepted Chief Joseph’s invitation to join Joseph and his family in the fall hunt at Nespelem, WA.

The following contain excerpts drawn from Wood’s essay.

“The Plastic Art of Treaty Making”

“The plastic art of Indian treaty making” is a history of “neglect, evasion, abrogation.” The Indians are removed from their native lands, once or many times until war results, or, “gifts, annuities and supplies are missing and war is the result. This displays promises unfulfilled and wasteful gifts and supplies demanded and committed to fraud.”

The Treaty of 1855 guaranteed Old Joseph’s band their new home in the Wallowa Valley. It was ratified by Congress in 1859, but in 1863, nearly six million acres of Nez Perce lands, including Wallowa and Alpowai, were seized and all Indians were ordered to the Lapwai Reservation. Old Joseph refused.

The 1863 Treaty was ratified by Congress in 1867, and signed by President Johnson in 1868. President U.S. Grant (a former army lieutenant who served at Fort Vancouver in the early 1850’s) signed the Executive Order of 1873 restoring the Wallowa Valley to Joseph’s band, now led by his son “Young Chief Joseph,” but by the President’s Executive Order of 1875 (also signed by Grant), Wallowa was “thrown open for settlement.” The band became “renegades” and they were ordered to Lapwai. War was the result.

“A Perpetual and Incessant Power”

“Scant supplies drove the Bannock nation to war. Supplies allocated for the Ute reservation Indians laid in storage for over a year while the Utes starved amidst aggravated cries for help. Hostile Pi-Utes claimed the same inexcusable treatment. Women, children and warriors perished at the hands of Indian agents and their colleagues from malnutrition and starvation.

“The Indian Department simply denied the existence of poor conditions to Washington, DC officials. They were several thousand miles away from the reservations and few had official authority to review or even deny the conditions.”

“Animated by the love of liberty and love of homelands, tribal peoples around the globe are brave and independent. A single battle did not decide the fate of the state.”

“The conquerors introduced agriculture and the game fled to thicker, unpenetrated forests. Indians had no choice but to follow. But within the span of two decades the landscape changed with such permanence, and Indian treaties became so distorted, that tribal people could turn neither back nor could they move forward.”

“Peoples cannot intermingle and yet remain separate as oil and water – neither predominating.”

The Euro-American is “mental; the Indian loves to live by hunting, requiring vast territories for a dwelling place. The white man loves to live by tilling the soil and he loves a fixed habitation. The Indian is as restless as the autumn leaf yet pines when removed from his habitat, the white man can give up his cherished home and cheerfully support an almost solitary life. The Indian has learned by acquaintance and tradition that the white man is a heartless intruder; the white man knows from experience and history that the Indian is a merciless savage. Their complexions and languages are totally different. In the contact of such opposed characters harmony is impossible. In the chafing which results, three participants may be noted on the chess-board: the Indian, the settler, and the government – the first two thoroughly antagonistic to each other and the last endeavoring to play the part of mediator and ruler. Vainly endeavoring, for the settler represents a perpetual and incessant power formative of the Government while the Indian’s influence is intermittent and indirect.”

“Nations, like individuals, whether through ignorance or arrogance disregard natural laws and assume omnipotence [and] the inevitable will bring them to shame. The United States pledged honesty but they pledged an honor they could not maintain. They made promises they could not fulfill.”

“Governing Indians with Indians”

Indians pressed onto one reservation were soon pressed off on to another. They saw their “guaranteed homes” occupied and mined by white people and the Indian lost faith, and bitterness unfolded. An increasing general distrust of white men and the American government resulted as they were “elbowed from place to place in defiance of promises, made foolishly because impossible to keep.”

The Indian has “no proper legal status” and “courts are practically closed to him; therefore a shot or a blow lights the torch of war.”

Government law allowed Indians the “right of occupancy only” – Not as an inherent right to all lands once roamed or prior to US Government “ownership.” Wood learned from Native Americans that they foresaw two great troubles: [the] “lack of assured possession of our homes and an absence of any means for the orderly redress of grievances.”

Due to the varying federal and state laws – “Though born in the US and aborigines of the country he is neither a citizen nor an alien.” He reminded readers of Chief Joseph’s statement before the Nez Perce War in 1877: “The greatest want of the Indians is a system of law by which controversies between Indians and white men can be settled without appealing to force.”

Wood expressed the Army’s vital interest in the Indian question and emphasized that it ought to be recognized because the Army had the greatest interface with Indians and settlers in the West. He stressed the value of education and assimilation among Indian people and concluded his proposal by urging that an Indian cavalry, not simply guides, be engaged from time to time. “It would give Indian soldiers a sense of pride and recognition of their knowledge and warrior attributes, as well as a “sense of governing Indians with Indians.”

In conclusion Lieutenant Wood restated the contemporary public consensus: “Indian war, not war.”