Confluence Bird Blind at the Sandy River Delta is a haven for contemporary birders to observe more than 60 species of birds and it serves as a poignant reminder of birds and wildlife of the past. Etched into the wooden slats of the blind are the names of the birds and animalia noted by Lewis and Clark during their journey between 1803-1806. A 2016 study of the contemporary endangered status of the 129 birds and animals gave some encouraging news. A 2016 study of the contemporary endangered status of the 129 birds and animals at the site gave some encouraging news. “The news is mixed, with some of these feathered, furred and finned animals increasing in number and some remaining rare,” said Bill Weiler, a wildlife biologist with the Sandy River Basin Watershed Council. [i] Designer and Confluence volunteer Dylan Woock painstakingly combed through multiple state and national databases to find out how those species are faring today. Turns out, in the last eight years several of the birds and animals have come off the endangered or threatened species list or are no longer considered “species of concern.” Click here (note to self: upload document) to see those returns.

Designed by Maya Lin, the Confluence Bird Blind at the Sandy River Delta is a haven for contemporary birders to observe more than 60 species of birds and it serves as a poignant reminder of birds and wildlife of the past. Etched into the wooden slats of the blind are the names of the birds and animalia noted by Lewis and Clark during their journey between 1803-1806. These species captivated people such as John Kirk Townsend, thirty years after Lewis and Clark canoed down the Columbia River. A young American ornithologist, Townsend, a young American ornithologist, secured sponsorship for a journey West to accompany Thomas Nuttall, a Harvard professor, botanist, and naturalist. The two were charged by their sponsors[ii] to collect many new species of flora and fauna as they crossed the plains and mountains to the Oregon Country. Once there, they were to broaden their studies to include as many species for identification as possible, collecting plant and animal specimens and sending them to the States by any means available. In addition to learning professional taxidermy, which then employed heavy use of toxic arsenic, Townsend was an accomplished scientist, alchemist and medical doctor. Often working together when they first arrived on the Columbia River in September 1834, the men began documenting and collecting many of the species seen by Lewis and Clark and many others that were entirely unknown to the newcomers.

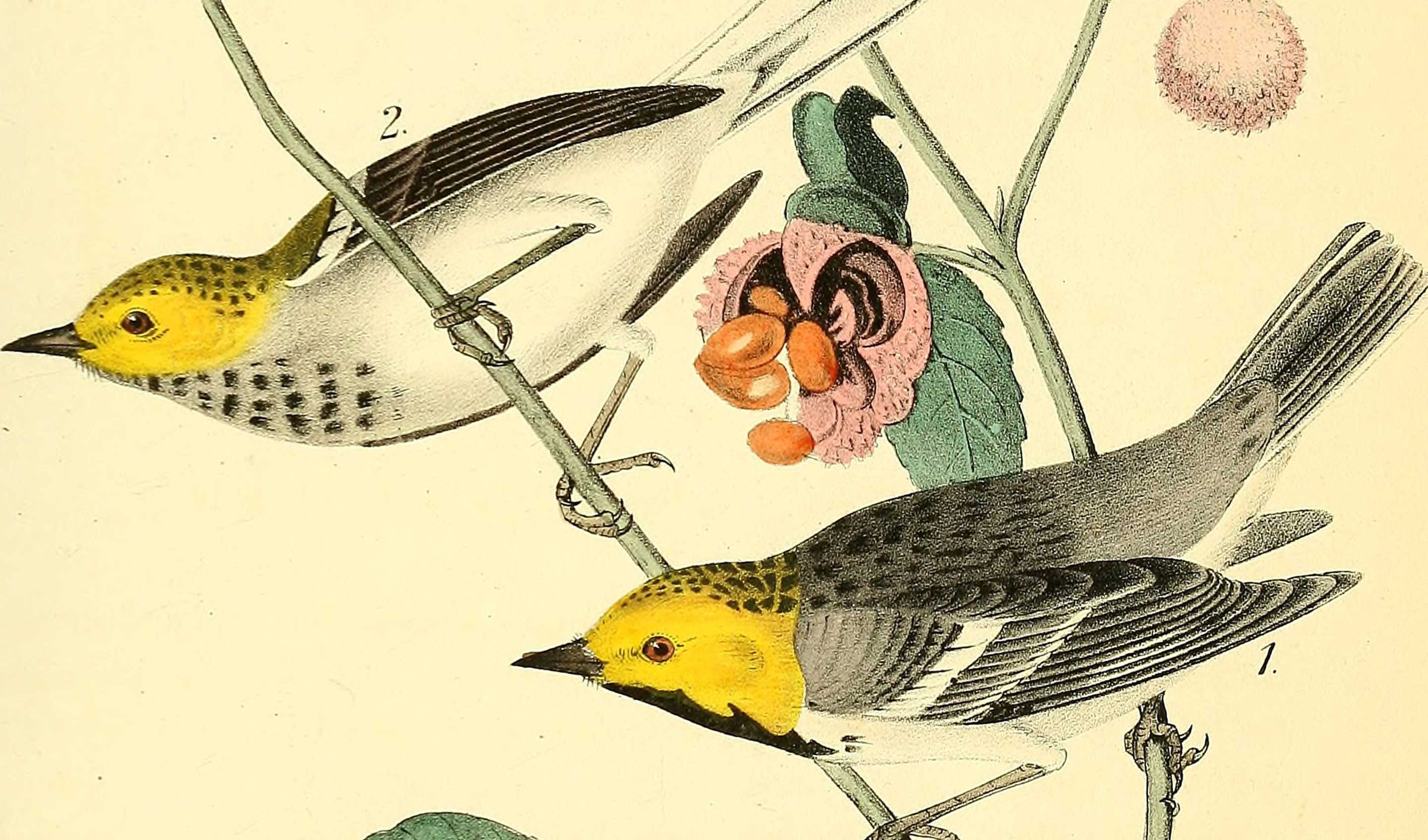

Several animals and birds bear the naturalists’ names, Nuttall’s Poorwill (Phalaenoptilus nuttallii), the Mountain or Nuttall Cottontail Rabbit (Sylvilagus nuttallii), and Nuttall’s Woodpecker (Picoides nuttallii – found mainly in California oak woodlands) were identified with the elder naturalist’s name. John Kirk Townsend is well remembered in the Northwest for Townsend’s Warbler (Setophaga townsendi), Townsend’s Solitaire (Myadestes townsendi), Townsend’s chipmunk (Neotamias townsendii), and Townsend’s mole (Scapanus townsendii.)

As the two men reached the Columbia River with the remnants of Nathaniel Wyeth’s expedition and two missionaries – Jason and David Lee – Townsend recorded in his journal: “the mallard duck, the widgeon, and the green-winged teal are tolerably abundant in the little estuaries of the river. Our men have killed several, but they are poor, and not good.”[iii] It was September 5, 1834, and the men were all eager to reach their destination of Fort Vancouver to learn if Wyeth’s supply ship, the Mary Dacre had safely arrived ahead of their overland party.

Fortunately, the sailing ship was on schedule, and was moored on the Willamette River, Townsend and Nuttall called the vessel “home” for the next 12 weeks. Townsend wrote, “[November] 5th.—Mr. N. and myself are now residing on board the brig, and pursuing with considerable success our scientific researches through the neighborhood. I have shot and prepared here several new species of birds, and two or three undescribed quadrupeds, besides procuring a considerable number, which, though known to naturalists, are rare, and therefore valuable. My companion is of course in his element; the forest, the plain, the rocky hill, and the mossy bank yield him a rich and most abundant supply.” [iv]

Dreary rain and chilly weather helped persuade the two naturalists to sail aboard the Mary Dacre to Hawaii in December 1834. They wintered there and returned to Fort Vancouver the following spring. Joyfully, they resumed their work of collecting and identifying plants and animals of the Columbia River region. They met many interesting characters, British, Americans, and indigenous people. But as 1835 faded into autumn and the gloomy rains returned, Nuttall became weary. It seemed that Townsend grew grumpy, too.

Townsend was known as the “bird chief” among the Chinookan people. He detested their dogs that snarled and snapped at him when he approached. His reputation preceded him (as well as his complaints about the dogs’ fleas) and villages were warned that Townsend would visit them. “Iskam kahmooks, iskam kahmooks, kalakalah tie chahko,” (“take up your dogs, take up your dogs, the bird chief is coming.”) They hid their dogs for fear that he would make good his threat to shoot every one on sight.[v]

Frequenting Fort Vancouver, Townsend grew fond of the in-depth scientific discussions he shared with Dr. Meredith Gairdner, Medical Officer of the Hudson’s Bay Company. The men held a common scientific interest and Townsend wrote with mixed sentiments, October 1, 1835:

“Doctor Gairdner, the surgeon of Fort Vancouver, took passage a few days ago to the Sandwich Islands, in one of the Company’s vessels. He has been suffering for several months, with a pulmonary affection, and is anxious to escape to a milder and more salubrious climate. In his absence, the charge of the hospital will devolve on me, and my time will thus be employed through the coming winter. There are at present but few cases of sickness, mostly ague and fever, so prevalent at this season. My companion, Mr. Nuttall, was also a passenger in the same vessel. From the islands, he will probably visit California, and either return to the Columbia by the next ship, and take the route across the mountains, or double Cape Horn to reach his home.”[vi]

Nuttall remained in Hawaii promising Townsend that he would soon return to the Northwest but he did not and bitterly, Townsend wrote to his family in April 1836:

“I think I told you in my late letter about Mr. Nuttall’s desertion of me. He went to the islands last fall to get rid of a disagreeable winter & promised me on the word of an honest man to return early in the Spring but instead of his corporal presence in the ship on her return, I found only a paltry note (I can’t call it a letter) saying that he was off, but not entering into any particulars of any kind not doing as my sister Hannah and all other people of the right sort would have done, telling me all about it & withholding nothing. He states his determination of going ‘round Cape Horn to Boston in a whale ship, but he changed his mind afterwards as I heard by a recent arrival, & has started on the very route that I proposed through Mexico . I have heard flying reports of difficulties between our government & Texas – hope there’s no truth in them – travelling might be rendered inconvenient.“[vii]

By the early 20th Century, Trumpeter Swans had been overhunted in North America for their skins and feathers – most often used for quill pens. Swans and geese were popular meats for the officers who hunted at Vancouver Barracks in the 19th century. By 1935, they were nearly extinct. The trumpeter swan is the largest waterfowl in North America and the largest swan in the world.

Townsend continued to perform his research in a variety of ways and keenly observed, “The ducks and geese, which have swarmed throughout the country during the latter part of the autumn, are leaving us, and the swans are arriving in great numbers. These are here, as in all other places, very shy; it is difficult to approach them without cover; but the Indians have adopted a mode of killing them which is very successful ; that of drifting upon the flocks at night, in a canoe, in the bow of which a large fire of pitch pine has been kindled. The swans are dazzled, and apparently stupefied by the bright light, and fall easy victims to the craft of the sportsman.”[viii]

After the departure of his close friends Nuttall and Gairdner, a dire homesickness gripped the young Townsend as he wrote to his family in Philadelphia. “I regret that I cannot yet speak with some certainty regarding the mode or time of my return. I am still favorable to the passage to England & think it most probable I shall embrace this opportunity. I shall however not recross the Rocky mountains – that’s decided, & if I choose a land route at all it will be through Mexico, after landing from the Sandwich Islands at Monterey, St. Francisco or some other port in California. The only objection to this is the considerable expense that must necessarily be incurred, but were I sure of the prompt assistance of the Acad. In these pecuniary matters I should not hesitate one moment, but choose this route & sail for the islands next month. I am however not sure of this & although I should certainly very much augment my collections in Nat. History by pursuing this course I fear that the prudential considerations will operate against the plan. I repeat that I am sorry, very sorry that I cannot speak with any certainty as to the time of my return, but I really think I can safely say that, choose what route I may I shall not be absent more than a year & 3 or 4 months longer. It seems a long, long time don’t it? Indeed it does to me; to look forward to a year appears like an age, but to look back on the time past is comparatively nothing.” [ix]

Seven months later, November 30, 1836, John Townsend stood at the rail of the bark Columbia and watched the Oregon coast grow faint in the distance. With slight regret, Townsend wrote in his Narrative: “Much as I desire again to see home,” he confided, “much as I long to embrace those to whom I am attached by the strongest ties, I have felt something very like regret at leaving Vancouver and its kind and agreeable residents.”[x] Townsend also experienced the satisfaction of accomplishment after two rigorous years’ residence in the Oregon Country studying and collecting the region’s largely unknown birds and mammals. With him was an immense collection of specimens of the then largely unknown species of birds and mammals from the Pacific Northwest. He was bound for America once more via Hawaii and South America.

Post Script:

When Townsend returned to Philadelphia in 1837, he was financially in a position to publish his new species without the assistance of John James Audubon or Thomas Nuttall. Soon after his return, he became a curator at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia and William Baird sang his praises to his brother Spencer Fullerton Baird (of Smithsonian fame). Townsend worked with the bird collection at the National Institute in Washington, DC, until, as George A. Jobanek wrote “controversies arising in relation to the United States Exploring Expedition led to his discharge.” [xi] Over 60,000 plant and bird specimens were collected on the Wilkes Expedition and many specimens were taken from regions that Townsend explored in the Oregon Territory and South America. The sheer quantity was overwhelming and many specimens may have been collected in a singular season whereas Townsend’s collection spanned nearly three years and often all four seasons. Tracking seasonal changes is essential to the naturalists’ taxonomy. U.S. Navy Lieutenant Charles Wilkes was unpopular with his men and was court-martialed on his return to Washington, D.C. These charges may have contributed to the controversy surrounding the distribution and identification to be exercised upon the immense collection given to the Smithsonian where Townsend was employed. It is likely that Townsend held strong views regarding the expedition’s collection of birds and for that, he may have been terminated.[xii]

Turning to the study of dentistry, Townsend waited patiently in the hope of joining an expedition to Africa. By 1851, his health was failing and his family suspected that exposure to arsenic was the cause. His brother-in-law wrote to Witmer Stone, another leading ornithologist, that he had often seen “John when employed by the government to mount specimens in Washington, bending over a big tray of arsenic, … enveloped in a cloud of dust.” Some believed the cumulative poison destroyed his health and ended his life prematurely in 1851 at age 42.[xiii]

End Notes

Listen and watch Townsend’s warblers: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hpQlILzavms.

[i] https://www.confluenceproject.org/news/confluence-bird-blind-species-list-updated/

[ii] The sponsors for Townsend were The Academy of Sciences of Philadelphia and the American Philosophical Society. Nuttall voluntarily agreed to join his friend Nathaniel Jarvis Wyeth in his second expedition to the Pacific Northwest designed to tap the commercial possibilities of salmon and fur trade. See George A. Jobanek, “John Kirk Townsend in the Northwest,” Oregon Birds 12(4):253-279.

[iii] John Kirk Townsend. Narrative of a Journey Across the Rocky Mountains, 1839. P. 157

[iv] Ibid. p. 177

[v] Ibid., p. 258

[vi] Ibid. p.233

[vii] John Kirk Townsend in a letter written to his family April 11, 1836 at “Fort Vancouver on the Columbia River.” Letter is from the archive at Drexel University in Pennsylvania.

[viii] John Kirk Townsend. Narrative of a Journey Across the Rocky Mountains, 1839. p. 234

[ix] John Kirk Townsend. Letter dated April 11, 1836 at “Fort Vancouver on the Columbia River.” Letter is from the archive at Drexel University in Pennsylvania. On March 6, 1836, Dr. W.F. Tolmie, a HBC surgeon, relieved Townsend of his charge of the Fort Vancouver hospital.

[x] George A. Jobanek. “John Kirk Townsend in the Northwest,” Oregon Birds 12(4):253.

[xi] Ibid. p.270

[xii] See this excellent account of the scientists on the Wilkes Expedition: http://www.sil.si.edu/DigitalCollections/usexex/learn/Philbrick.htm

[xiii] George A. Jobanek. “John Kirk Townsend in the Northwest,” Oregon Birds 12(4):. 270