Fort Astoria Became Fort George As Ultimate Control Was Undefined

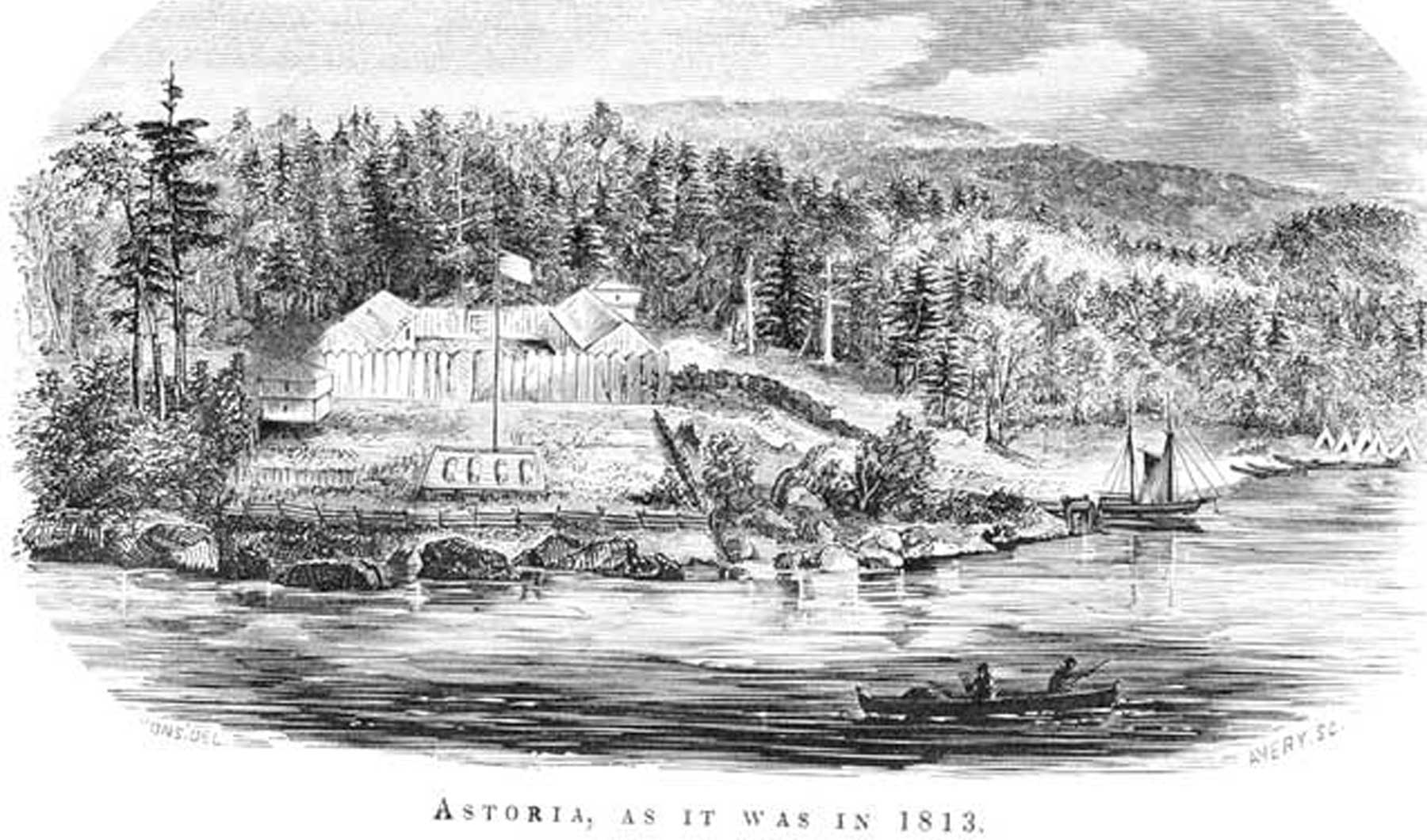

Less than six years after Lewis and Clark camped at Fort Clatsop for the winter, John Jacob Astor sent ships to establish the first permanent American settlement west of the Rocky Mountains. It was named Fort Astoria. Due to the War of 1812 and the fragmented political controversy between Britain and the US, the polyglot of Americans, Scots, French Canadians, Hawaiians and regional and continental indigenous people all trading at Fort Astoria soon became confused about the world’s dominance at the tiny fur trading post on the Pacific Ocean. By 1813, ownership passed to the North West Company (Canadian) and the place was renamed “Fort George.” At the end of the war, under the agreement of the Treaty of Ghent, legal ownership was restored to the Americans.

It must have looked like a comedy of errors to the native people of the Columbia River when American Captain James Biddle of the flagship U.S.S. Ontario arrived off of Cape Disappointment on August 19, 1818. There, the captain landed 150 troops near the present Cape Disappointment Coast Guard Station, hiked to the summit, nailed a lead tablet to a tree, turned a ceremonial spade of earth, saluted the flag and claimed the vast area – the entire region of the Columbia watershed— for the United States. Biddle claimed both sides of the river and next sailed south, touching at Monterey, California, for supplies, becoming the first American naval vessel to visit the three future Pacific coast states. [1]

Just two months later (October 1, 1818) the British frigate Blossom, Captain Frederick Hickey, entered the river, anchored and repeated the Americans’ action but claiming the land instead for Great Britain. The U.S.S. Ontario departed when the Blossom arrived, leaving British fur traders in a quandary unsure whether peace or war existed. They had made preparations to defend the post. [2] The dispute over ownership continued, but much to the surprise of the Fort George occupants, Captain Hickey and James Keith, a British commissioner and the Factor in charge of the fort, signed the Instrument of Restoration to the United States. The British flag was lowered and the Stars and Stripes were raised over Fort George – intending to symbolize American “ownership” of Fort George (perhaps in the middle of British Oregon Territory!) The Canadian Nor’westers continued to use the post as their headquarters on the Northwest Coast. It remained the chief depot of the Hudson’s Bay Company, which merged with the North West Company in 1821, until 1825 when British Fort Vancouver was dedicated up the river. [3]

An Era of Trade Brings Scientific Explorers and Western Religions

The British ship William and Ann approached the Northwest Coast after long arduous months at sea wherein two adventurous young men, one a botanist and the other a ship’s surgeon who studied geology and zoology, eagerly anticipated their arrival at Cape Disappointment. Finally on April 3, 1825, David Douglas recorded that an easterly breeze brought them within four miles of the “maw” of the Columbia, but a “violent storm from the west obliged us again to put to sea.” [4] Two days later, Douglas and the ship’s doctor John Scouler helped mark the depth sounding as they eased over the Columbia River’s dreaded bar. A northwest wind allowed that

“such an opportunity was not lost, all sail was set, joy and expectation was on every countenance, all glad to make themselves useful. [5]

The ship’s captain fired cannon shots to announce their arrival to traders at Fort George, but no answering shots were returned. The two young naturalists did not care, for they had been at sea more than eight months and David Douglas wrote,

“the joy of seeing land … and the pleasure of again resuming my wonted employment may readily be calculated…. With truth I may count this one of the happy moments of my life.” [6]

John Scouler recorded in his journal of April 9,, 1825, from their safe anchorage in Baker’s Bay:

“We were this morning pleased by a scene that was new to all of us, several canoes were seen approaching the ship & in a short time three of them were alongside of us. On coming on board they behaved with the utmost propriety …. “

Noting that the native people seemed “unsettled” due to circumstances unrelated to their ship’s visit, Scouler’s account continued,

“The dress of the men consisted of a robe of skin, which was thrown loosely over their shoulders, & alike useless for the purpose of decency or of comfort. Their hats were made of straw very neatly plaited, and were of a conical sugar loaf shape. The dress of the women was more decent, & consisted of a petticoat which reached to the knee. It was made of many strings placed exceedingly thick together & must afford considerable warmth. Over this they wear the same skin robe as the men. “ [7]

The following day, the two naturalists ventured onto the Columbia River and again Scouler had much to say about their first impressions:

“In the afternoon in company with Mr. Douglass I made a short visit to the shore. The first we collected on North American continent was the charming Gaultheria Shallon [Salal], in an excellent condition. We then penetrated into those primeval forests never before explored by the curiosity of the botanist. Here the lover of musci [mosses] & lichens enjoys ample opportunity of studying his favorite plants. The moisture of the climate is very favourable to the growth & variety of these plants & the trees & rocks are covered by them. During this excursion we saw none of our new friends, the Indians.” [8]

Compiling his geological notes after a visit at Cape Disappointment and Fort George of several days, Scouler wrote:

“ From the soft nature of the rocks of the Columbia & from the great size of the river during the summer months, immense quantities of sand are deposited in different situations. From the abundance of these materials the numerous alluvial islands of the Columbia are deposited & banks & shoals are formed in every part of the river. These islands are some of them two or three miles in extent, & would afford the richest agricultural returns, if they were not annually covered by the waters of the river during two months of the year. … All the mud & sand of the river is not thus deposited; part of it is carried out to the ocean, & by the action of the Westerly winds, which blow three fourths of the year, it is accumulated at the mouth of the river & forms the chief danger of the navigator who visits the Columbia.” [9]

Among the newcomers to Cape Disappointment were those interested in the people who already lived there and in the 1820’s, they were predominantly Chinookan people. The Missionary Herald of April 1831, reported on the exploring tour on the Northwest coast in 1829 by Reverend J.S. Green. The protestant minister was fulfilling duties for the American Board of Foreign Missions.

At the conclusion of his report, Reverend Green wrote:

“…For more than forty years, our enterprising countrymen have coasted these shores, and realized immense profits from their commercial intercourse with the natives. Surely, the American church will not regret, even should nothing more be done, that a few hundred dollars have been expended to investigate the moral condition, and to ascertain whether anything can be effected, to relieve the moral necessities, of a multitude of our fellow men, for whom the Savior died. An honest statement of the condition and prospects of these men … are discouraging circumstances.” [10]

Thumping bibles, trading furs or carrying spades, newcomers to the Columbia River generally introduced new cultural practices, languages and beliefs. As the Hudson’s Bay Company built new posts along the entire length of the Columbia, settlements composed of foreign nationalities began to thrive. At Fort Vancouver, the efforts of doctors and naturalists encouraged the propagation of seeds, crops and animal husbandry (sheep, cattle and hogs) previously unknown in the region. The demands on the ecology of the land and river were altered, too. Plains and forests were cleared; sawmills and grist mills were built, and salmon fishing became an “enterprise” of the Hudson’s Bay Company in the early 1830’s. Rivers and streams served as water highways between posts and Willamette settlements and soon missionaries built meeting houses and schools. The accustomed native traditions and trade were severely interrupted as cultures clashed and American settlers experimented with the creation of new communities in the Northwest. Naturally, suspicions and mistrust grew as settlers claimed native lands and the rights to rivers and streams that were central to the cultures of Native Americans. In the 1830’s, the most devastating war on tribes came in the form of disease that could not be cured with traditional medicines or practices.

For foreigners in this land, Cape Disappointment was no longer “disappointing” as it became for many the gateway to a prosperous future. But the tide had turned, and all that the Cape promised to newcomers soon became an adverse change,great disappointment and grief for the original inhabitants of the Columbia River and its tributaries.

End Notes

[1] Longstaff, F.V. and W. Kaye Lamb. “The Royal Navy on the NW Coast, 1813-1850, Part I.” British Columbia Historical Quarterly 9 January 1945. 6.

[2] Gough, Barry M. The Royal Navy and the Northwest Coast of North America 1810-1914. British Columbia: University of British Columbia Press, 1971. 27-28.

[3] Nisbet, Jack. The Collector. Seattle: Sasquatch Press, 2009. 34.

[4] Ibid. excerpt from David Douglas’s 1825 journal.

[6] Scouler, John. “Dr. John Scouler’s Journal of a Voyage to N. W. America [1824-’25-’26.] II. Leaving the Galapagos Islands for the North Pacific Coast.” The Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society 6 no. 2, June 1905. 163. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/20609647.pdf

[8] Quoted here with original spellings.

Author’s Note: Like many who followed, Scouler was insensitive to native burial practices and sites. As a physician he viewed burial grounds as a “scientific” opportunity to collect specimens and data for study. He spent many hours on Mount Coffin studying human remains in the burial canoes, particularly one that was damaged. As he left the Oregon Country, Scouler stole several skulls from burial sites, and on his return to England, Scouler became the first to publish a scientific article on Northwest Indian skulls. See http://www.ohs.org/research-and-library/oregon-historical-quarterly/upload/04_Lindquist_Stealing-from-the-Dead_OHQ-115_revised.pdf.

[10] Green, J.S. “Extracts From the Report of an Exploring Tour on the North-West Coast of North America in 1829.” The Missionary Herald 26. 1830. 343.