Dogs and their owners love to roam at every Confluence site along the Columbia River system, a combo that has likely lasted for at least five to ten thousand years. Dogs lived among many of the Native American tribes and most were raised as working dogs, hauling belongings on a travois, herding animals, or as a constant source of fur for weaving. Many tribes ingeniously trained their dogs to help hunt bear, elk, deer, mountain sheep and water fowl. Elk and deer were driven by dogs into the hunting snares. [1] Most were also faithful companions that acted as a security alarm when strangers approached their villages or camps.

Domestic dogs as well as wild dogs – wolves and coyotes – play strong roles in Native American legends. Dogs were present in most of the Native American camps from the Chinook villages at the mouth of the Columbia to the Nez Perce settlements at Lapwai.

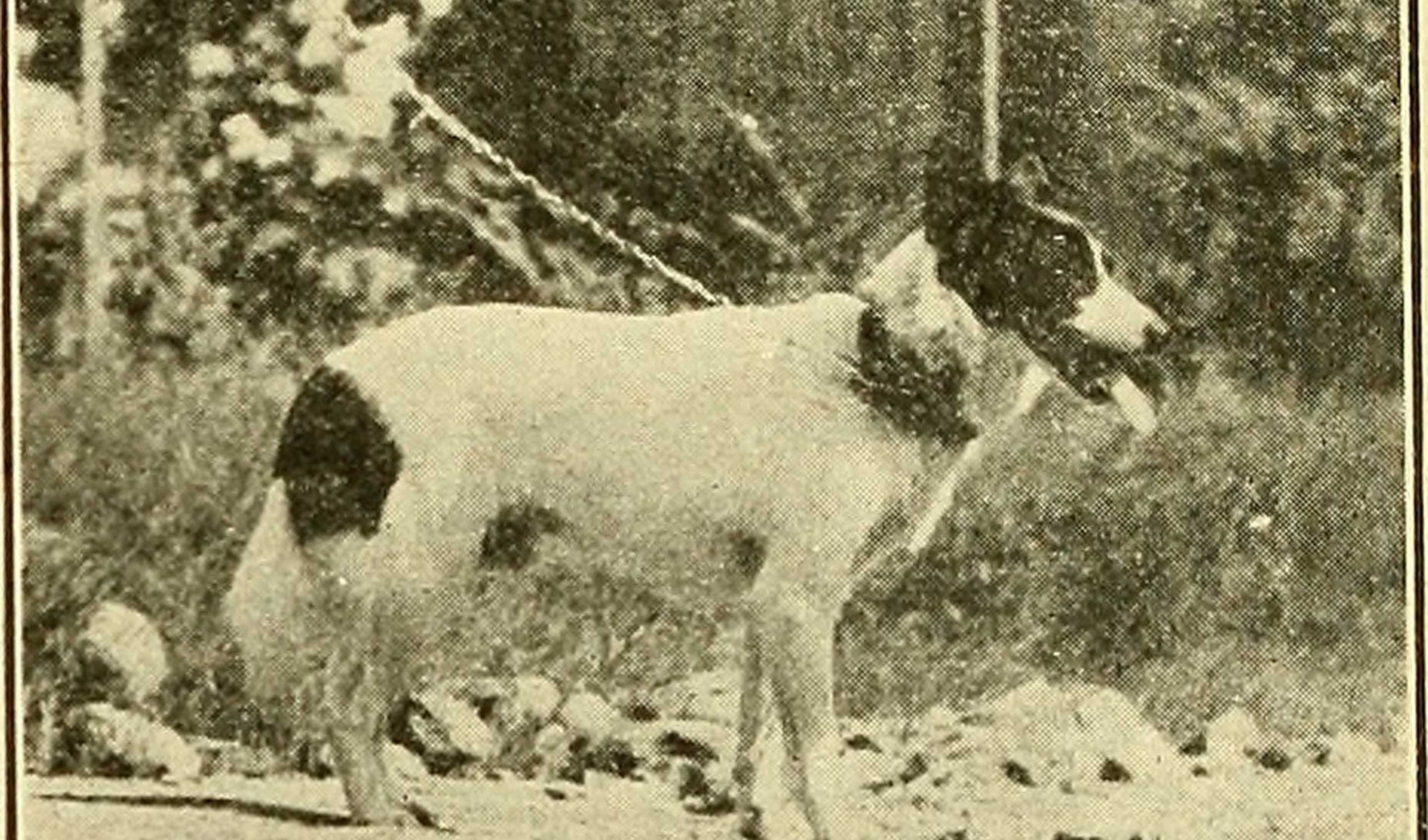

Rarely were domestic dogs used as a food source. Some foreigners, however, had surprisingly different tastes when they approached tribe’s camps. Among the Nez Perce, there were many dogs and many jobs for them to perform. Meriwether Lewis described their dogs in 1805 as being: “party coloured; black white brown and brindle are the most usual colours. The head is long and nose pointed eyes small, ears erect and pointed like those of the wolf, hair short and smooth except on the tail.” [2] The Nez Perce and other upper Columbia River “Plateau” tribes raised dogs. Their breed was known as “Tahltan Bear” dogs. They were small short-hairs with huge ears and they closely resembled the Pueblo dogs of the tribes of the Southwest.

Unlike William Clark, Lewis grew fond of dog meat as a substitute for wild game. Many in the Corps of Discovery grew ill from the dried fish and wild camas supplied by tribes west of the Rocky Mountains and when game grew scarce, they traded for tribe’s dogs for a taste of red meat. Some native people held this consumption in great disdain. [3]

It seems even more peculiar because Lewis was the single member of the Corps who brought along his dog named “Seaman.” A young Newfoundland, Lewis paid $20 for the fine companion. The dog was likely the only true recipient of Lewis’s affection – a loner, Lewis was a difficult person who rarely enjoyed the company of others.

Lewis considered Seaman a useful hunter, too. On the Ohio, September 11, 1803, Lewis wrote: “…Observed a number of squirrels swimming the Ohio and … I made my dog take as many each day as I had occasion for. They were fat and I thought them when fryed a pleasant food.”[4] Seaman grew to weigh over 150 pounds. Native Americans offered high trading prices for Seaman but Lewis would never part with him. It is believed that Seaman survived the entire journey and was nearby when Lewis died in 1809.[5]

There are references to fur traders, trappers and Hudson’s Bay Company men travelling west with their dogs. Soon preachers, developers and wagon trains began crossing the prairies to the west coast and they, too, brought along dogs – small to big – to populate the communities up and down the Columbia River. One of the most popular in the annals of botanical science was a little Scotty named “Billy.” His master (or perhaps it was the other way around) was the young Scot, David Douglas. Billy came along with Douglas on his third and final trip to the Pacific Northwest. With the plucky little Scottish terrier at his side, Douglas sailed from London to Fort Vancouver in 1832. By then, the Fort farmed hundreds of acres in grain and corn, and tended a six-acre garden and orchard where they attempted to grow all kinds of species of plants. Douglas was instrumental in helping them cultivate new crops with visionary ideas, grafting and crossing saplings and seeds.

With Native American scouts who knew the territory, Douglas and Billy tramped forests, plains, and deserts for thousands of miles in search of new flora species. Describing and collecting his specimens along the way, Douglas and his dog were often the only two who understood English within a thousand mile range. The tribes had a myriad of languages and dialects, and the Hudson’s Bay people spoke mainly French away from Fort Vancouver. Botanist and dog made good companions. Douglas sought the permission of the Hudson’s Bay Company to roam north through the Yukon and cross over to Russia through Russian-Alaska, if weather permitted, camping at Hudson’s Bay Company trading forts along his lonesome trek. Permission was granted with many heartfelt warnings for the headstrong naturalist.

The dog and the botanist set out on their journey north through the Cascade and Olympic Mountains and along the Pacific Coast. They hitched rides with Hudson’s Bay Company canoes whenever possible, meeting Company men who were Metis and Iroquois.

At Fort Yukon, Douglas realized that frigid weather and rough terrain were two great obstacles that could not be overcome that season. He and the little Scottish terrier turned south once more. They rested through the autumn of 1833 at Fort Vancouver and then at the Chief Factor’s invitation, they joined one of the Fort’s hunting parties on a trip to California. Billy stayed with Douglas until Douglas’s death in 1834, after which he was sent back to Scotland.

End Notes

[1] Unknown. “History of the Native American Dog.” Majestic View Kennels Hypoallergenic Dogs!. http://www.godsdogs1.com/history-of-the-native-american-dog.html

[2] Hunter, Francis. “Dog: It’s What’s for Dinner.” Francis Hunter’s American Heroes Blog. October 14, 2009. https://franceshunter.wordpress.com/2009/10/14/dog-it%E2%80%99s-what%E2%80%99s-for-dinner/

[3] Ibid.

[4] Albers, Everett C. The Saga of Seaman. North Dakota: Northern Lights Press, 2002. 3.

[5] Holmberg, James. “Loyal to the End?” Discovering Lewis & Clark. December 2012. http://www.lewis-clark.org/article/2295