Author Bio: Emily Washines, MPA, is a scholar and enrolled Yakama Nation tribal member with Cree and Skokomish lineage. Her blog, Native Friends, focuses on history and culture. Building understanding and support for Native Americans is evident in her films, writing, speaking, and exhibits. Her research topics include the Yakama War, Native women, traditional knowledge, resource management, fishing rights, and food sovereignty. Emily speaks Ichiskiin (Yakama language) and other Native languages. Yakima Herald-Republic lists her as Top 39 under 39. She received a Single Impact Event Award for her 2018 presentation from the Association of King County Historical Organizations. She is a board member of the Museum of Culture and Environment, Artist Trust, and Columbia Riverkeeper. She is adjunct faculty at Yakima Valley College.

Growing up in the Northwest, we hear a lot about fish. But how do children learn about fish and who teaches them?

For Native people, that knowledge is passed down to younger children through telling our history, culture, and lifeways. Since time immemorial Native people have lived along the Nch’i Wāna (Columbia River) and for generations, knowledge is acquired about the resources and the rivers then passed down through the generations through storytelling. Fish are intertwined with River Peoples’ past, present and future.

The purpose of this article is to help prepare educators to include teachings from Native peoples about fish, history, and ongoing fishing relationships. The article highlights several important points to know, as well as multiple resources teachers can utilize in the classroom. We will discuss the importance of teaching about 7 fish in the Nch’i Wāna (Columbia River) and how tribal identity is intertwined with the river and fish.

Importance Of Fish In Education

Children relate to the natural world around them. Years ago, my young daughters were at the pool that had a shallow rocky edge. They said, “Look, mom, I’m a sockeye.” As I looked, they were laying flat on their tummies with their heads turned above the inches of deep water. In Cle Elum, Washington, sockeye were spawning in the shallow clear water, our children remembered watching the females as they used the rest of their energy to swim above their eggs. They imitated them.

As a Native American parent, there is some uncertainty when asking for Native history to be taught. Seeing the list of assignments for students, we may question whether there is enough room. I gathered a couple of Native students to ask what they learn about fish in the classroom.

My daughters are in the 5th and 6th grades in public schools on the Yakama Reservation. My oldest, Alice, recalls in the 1st grade they talked about fish before a field trip to the zoo. My youngest daughter Zora only recalls learning about fish when she was 4 years old with a Yakama teacher, telling me that “In Head Start, we learned about my culture.” She awaits future lessons in school

“In Indian Club, we talk about legends and our fish,” said my daughter Alice, referring to a weekly after-school program for Native American Children. Their regular classrooms do not incorporate many lessons about fish.

Several years ago, as a guest speaker on fish for a school on the Yakama Reservation with hundreds of kids in the gym listening. Some students lit up as they connected to the presentation. There was one student that I remember the shine in his eyes as he chatted about fish and the Yakama language. He was proud of this inherent knowledge. Many of us hope that this relationship is understood, honored, and included by educators.

Natives often see a disconnect between what we learn in the classroom and the oldest dataset in the Northwest – Native American Knowledge. Educators should understand and honor the relationship with tribes and the resources.

Are educators prepared to include teachings from Natives about fish, history, and ongoing fishing relationships? Some have taken steps to address this, such as curriculum in classrooms written by Native teachers and by consulting with Native educators and Elders. Techniques such as participatory learning may parallel how Native American children are historically taught. One example is fish release events that connect children with the river, such as La Salle’s High School (Yakima, WA) “Salmon in the Classroom” program, which consults with the Yakama Nation Fisheries, and the May salmon release at Sacajawea State Park (site of the Confluence Story Circles) in Pasco, WA. Hearing our elders share words of wisdom about fish at ceremonies is important. Therefore, including elders’ words alongside classroom learning is crucial. We can hear some Native peoples talk online in the Confluence Library.

There are a handful of states — including Washington, Oregon, and Montana — that have passed laws that require public schools to teach Native history and sovereignty. Washington’s curriculum development and training of teachers has been going on since 2006 and is available at the Office of Superintendent’s website Since Time Immemorial. [1] Washington’s curriculum development and training of teachers has been going on since 2006 and is available at the Office of Superintendent’s website Since Time Immemorial. Teachers need resources and can connect fish to their lesson plans.

There are a few pathways including but not limited to the following:

- Educators build upon and include Native History in the curriculum they teach

- They have guest speakers talk to the students

- A mixture of classroom learning from the teacher and guest.

To teach about the fish in the Columbia River there needs to be information we can access. The first step is to learn what the seven fish that call the Columbia River home are and why they hold importance for tribes. This is one such resource for teachers.

Seven Fish to Know (Alphabetical Order in Ichiskiin)[2]

The Yakama Nation published a webpage with materials to help k-12 teachers. “Here, educators will find additional tools and resources developed by Yakama Nation Fisheries that can be used to help shape curriculum further or enhance classroom lessons, especially around the importance of fish as it relates to tribal history, culture and economics today.” The activities placemat shares images and info for six fish species as well as the Yakama ceded area. This includes a couple of words in the Ichiskiin language. [3]

Native American Language in and of itself is a data set. Therefore, it is imperative to learn the names that the fish have been called for thousands of years on this river. The Ichiskiin language is also utilized in the list of fish below. There may be variations with dialects.

The fish are in alphabetical order by their Ichiskiin names.* 1. Asúm (eel-like lamprey) 2. Kalúx (Sockeye) 3. Shusháynsh (Steelhead) 4. Sinux (Coho) 5. Tkwīxnat (Chinook) 6. Wílaps (White Sturgeon) 7. Wilxina (Smelt)

- Asúm (eel-like lamprey)

- Kalúx (Sockeye)

- Shusháynsh (Steelhead)

- Sinux (Coho)

- Tkwīxnat (Chinook)

- Wílaps (White Sturgeon)

- Wilxina (Smelt)

*to learn more about the Ichiskiin language, go here.

Each fish has a paragraph followed by five facts in bullet format for ease of use by educators that want to utilize them in a lesson or PowerPoint.

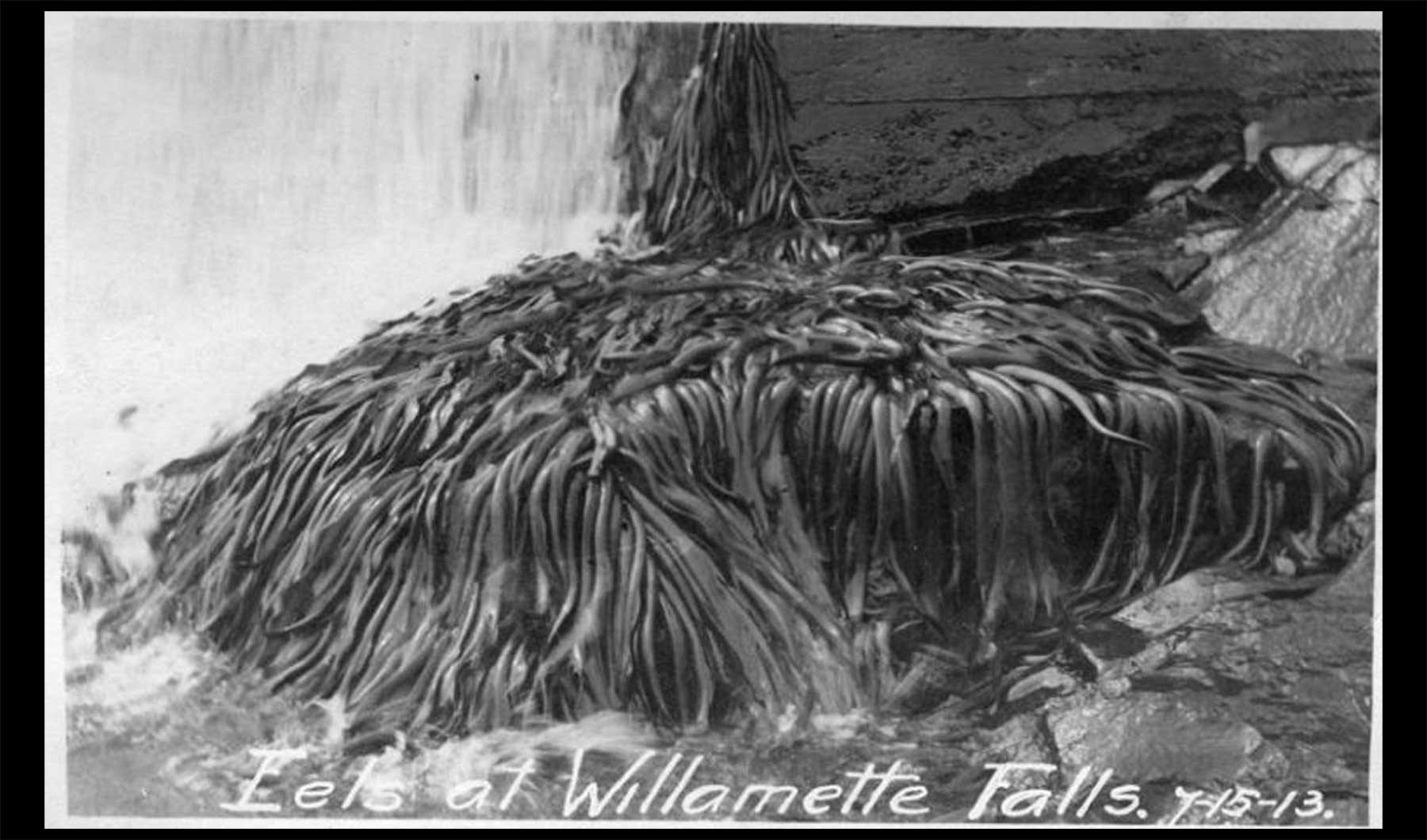

Asúm Eel-like Lamprey

At a young age, I saw asūm on the ceremonial tables and heard legends about them from our elders. According to a Yakama Nation factsheet, “Pacific Lamprey are among the planet’s oldest living vertebrates—predating dinosaurs by as many as 200 million years. Though they have survived for millions of years, their population in Washington state is in severe decline, dropping by 90 percent in some areas due to pollution and the damming of lakes and rivers since the early twentieth century.”[4]

Some facts about Asum (eel-like lamprey):

- “A traditional food staple and ceremonial fish for the Yakama people, Pacific Lamprey play a critical role within the Columbia River ecosystem.” [5]

- “Lamprey are eel-like fish that spend one to three years in the ocean before returning to spawn.” [6]

- “Like salmon, Pacific Lamprey do not eat when they swim up river to spawn.”[7]

- Asūm is one of the traditional names for this fish. In recent times, the term eel and lamprey are used.With contact, they translated “asum” to “eel.” Yakamas often use the word from that translation time period. In recent years, scientists have corrected this to Pacific Lamprey. A term that includes both the historically translated term and the recent correction is eel-like lamprey. [8]

- In this excerpt, Dr. Virginia Beavert tells how rattlesnake challenged eel to race, to try to steal eel’s identity

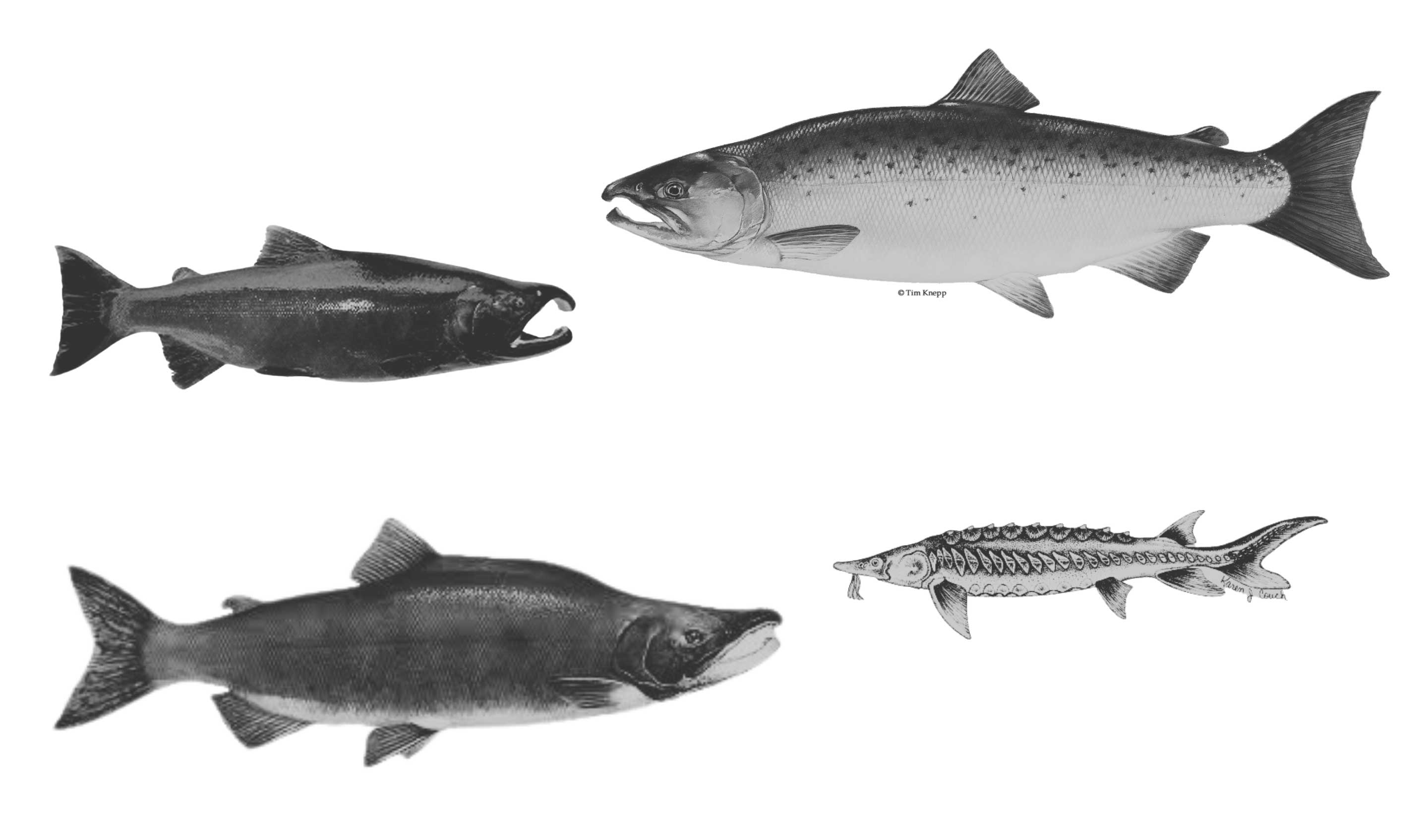

Kalúx (Sockeye)

The Yakama Nation talks about the number of kalux in one subbasin of the Nch’i Wāna. “A century ago, sockeye runs that historically produced [at least] 200,000 fish each year were obliterated in the Yakima Basin. Victims of the heyday of dam building in the early 1900s…sockeye salmon simply disappeared as the man-made structures blocked passage to their traditional spawning grounds.”[9] In the Yakima basin, the fish were extirpated, which means locally extinct for 100 years until the Yakama Nation’s scientists reintroduced sockeye in 2009. Our Elders were along the water to bear witness.

5 facts about Kalux (sockeye):

- “Yakama Nation Fisheries launched the Yakima Basin Sockeye Reintroduction project in 2009.” [10]

- “Sockeye travel hundreds of miles and climb thousands of feet to spawn, where females release an average of 3,500 eggs.”[11]

- “Sockeye spend one to three years in lakes close to where they were born before they swim to the ocean.”

- “During spawning, male Sockeye grow a hump on their backs that they use for fighting other male Sockeye.”[12]

- Kalux (sockeye) were locally extinct and after a 100-year absence returned to the Yakima River Basin from restoration efforts by the Yakama Nation.

Shusháynsh (Steelhead)

Most fish are only able to spawn once. “Columbia River steelhead are iteroparous (able to spawn multiple times). However, as post-spawned steelhead (kelts) attempt to migrate downstream to return to the ocean, their survival is adversely affected by major dams,” writes Douglas R. Hatch, a fisheries scientist at the Columbia River Intertribal Fish Commission. [13] The Yakama Nation helps the steelhead by reconditioning the fish that just spawned. This process includes feeding them to help them lay eggs again.

5 facts about Shusháynsh (Steelhead)

- “Wild steelhead kelts from the Yakima River are captured during their migration past Prosser Dam and through the Chandler Canal.”

- The steelhead kelts are held at a “…hatchery for up to 10 months, then released to the Yakima River…” [Yakama Nation][14]

- “Steelhead are trout that migrate to the ocean before returning to spawn after two years. About 10-15% of steelhead don’t die after spawning.” [15]

- “Did you know that steelhead is actually a trout species?”

- “There are two types of steelhead: summer steelhead and winter steelhead.” [16]

Sinux Coho

The Yakama tribe made restoration efforts for sinux (coho). “During the pre-treaty era, 44,000 to 150,000 coho returned to the Yakima Subbasin annually. By the mid-1980s they were extinct. Habitat loss and overharvest are factors that led to the extinction.” There is a goal to restore the coho populations that historically spawn in tributaries of the Upper Yakima Subbasin that will “…support sustainable harvest and are consistent with tribal and regional ecosystem restoration objectives.” .[17] The fish life cycle includes the Columbia River and other subbasins including the Yakima Subbasin.

5 facts about Sinux (Coho):

- “Coho salmon turn red in the fall of their third year as they begin to spawn, where they deposit 3,000-4,000 eggs,” [18]

- “While some salmon swim a long way into the ocean, adult Coho stay near the shore.”

- “Coho are extraordinary fighters and the most acrobatic of all Pacific salmon.”

- “Because their breeding grounds are small, Coho spread out and spawn in several locations.

- “Young Coho defend their spawning territories by doing a shimmy shake, which scientists call a “wig-wag dance.”[19]

Tkwīxnat (Chinook)

“Today, some say there wouldn’t be salmon in the Columbia if it weren’t for Yakama Nation Fisheries and its innovative projects.”[20]

~ Yakama Nation Booklet

Scientists help Spring Chinook through a research and supplementation facility in Cle Elum, Washington. “We implement factorial mating which increases genetic diversity,” said Charlie Strom, Yakima Basin Production Coordinator with the Yakama Nation.[21] During tours, you can see crews that include Yakama tribal members that studied to be scientists or technicians.

5 facts about Tkwinat (Chinook):

- “Spring chinook are the largest salmon species. They take cover in deep pools before traveling along the Columbia to spawn in tributaries.”[22]

- “Chinook are the largest of all salmon species and are sometimes referred to as “king” salmon.”

- “As the largest of all Pacific salmon, Chinook are the favored food of Orca whales.”

- “When they spawn, male Chinook develop a hooked snout or nose.”

- “To reach the areas where they were born, adult Chinook swim upstream for up to 60 days.”[23]

Wílaps (White Sturgeon)

The Yakama Nation is helping a very large fish — sturgeon can be up to 20 feet long. “The long-term goal of the Yakama Sturgeon Management Project is to restore healthy, harvestable populations and fisheries for white sturgeon in mid-Columbia River and Lower Snake reservoirs.” This work began in the 1990s with a small number of sturgeon. There is a Yakama sturgeon hatchery in Toppenish, WA.[24]

5 Facts about Wílaps (White Sturgeon):

- “White sturgeon are the largest freshwater fish in North America and can live to be more than 100 years old.”[25]

- “White Sturgeon do not have teeth. They eat by sucking in their food.”

- “Instead of scales, White Sturgeon have boney protrusions called “scute.”

- “White Sturgeon spawn many times in their lives, though females do not lay eggs every year.”

- “White Sturgeon grow slowly and don’t spawn until the females are at least 18 years old and the males are 14 years old.[26]

Wɨłxɨna (Smelt)

I discuss wilxina in this article, writing that “The Columbia River binds our region together. It provides our sacred first foods. It is where Yakama tribal members exercise our treaty rights to take salmon, eel-like lamprey, sturgeon, and smelt.”[27] Smelting is often a time when youth, adults, and elders go to the shores to bring this fish to the table. Historically this included the Cowlitz River and Sandy River. Teaching the youth to bring fish for their families and other members in the tribe connects to the teachings about being a provider.

5 Facts about Wilxina (Smelt):

- Smelt is a small fish, about 6-9 inches. It has a silver/white side and belly, with a long thin body combined with a skinny head and large mouth.

- A small fish that is enjoyed by Native people. When there is a season, Yakama Nation will send a crew to dip for smelt to provide fish for tribal members.

- Pakiyawaxa wɨlx̱ɨná is the original name for Sandy River, a tributary of the Columbia that flows through what we now call Oregon.

- It is from the legend of wɨlx̱ɨná’s origin is from which the Sandy River gets its Yakama place name.

- Coyote stopped wɨlx̱ɨná (smelt) from following Tkwinat (Chinook). He told them, “…you are needed at the end of winter when the humans will be very hungry, not when we have all this salmon in the spring. Come back earlier but you must go to the other tributaries.” [28]

Fish Intertwined with Identity

This Confluence interview with Yakama elder and educator Patricia Whitefoot discusses identity that includes her connection with the resources as well as Native erasure in school.

“The land holds a very special and sacred place to me where I was raised as a young child and continues to hold a very special place to me as a grandmother and a great-grandmother today because it’s that particular knowledge and understanding that I continue to share with my grandchildren today about who they are, where they come from and how they relate to the wider world.” ~ Patricia Whitefoot.

She shares an experience as a child when Patricia’s teacher told her Columbus discovered America. When she went home her grandmother corrected that information and told her, “That’s a lie!” For Patricia, her experience impacted her to this day. “When I look at textbooks or curriculum or any type of curriculum…I look at it very seriously simply because of that experience that I had with my grandmother. For me, the truth is the oral traditions that I grew up with, the history that my grandparents shared with me about who I was,” she explains.

There are also examples of family trips that are important for learning.

“[We] Annually traveled to Celilo to where the Dallas Dam was and had the wonderful fortune to travel with grandparents, my grandfather, mother, and uncles who fished there annually,” Patricia Whitefoot recalled. Because of that relationship that we have with the river, with the salmon, and again with the plant life around that area I feel a very heavy responsibility to that environment…” ~ Patricia Whitefoot

Our Fish Knowledge

The knowledge of fish is not just stagnant in books or pictures. This knowledge is carried by generations before us and passed down to generations not yet born. In this personal interview Brian Saluskin illustrates the intertwined relationship of being a fisherman as well as a biologist:

As a Tribal Fisherman, it’s been our livelihood for generations. I grew up eating salmon for every meal and put school clothes on our backs every year. It’s equivalent to harvesting a farmer’s crop, we harvest salmon. It’s why we take care of the resource and don’t over harvest. Take what we need and or allotted by our monitors. This is not a sport for our people by a way of life not only physical but spiritual. We honor the resource in our Ceremonies and Prayer to continue to live this way of life. It’s not just for today but as a Tribal people, we’re always considering the generation to come, our children, children’s children, and those to come.

This is the reason we fought so hard to maintain our Treaty Rights protected by the Constitution of the United States, the Law of the Land. It’s also the reason I became a Fisheries Biologist for the Yakama Nation to give back to the resource and my people for the next generation.

– Brian Saluskin[29]

Many examples illuminate how Natives’ eyes shine bright when talking about fish. From a Yakama perspective, that light in our eyes connects to the water, the silver scales of the fish as they swim upstream so they can blend with the water to camouflage from predators. For generations, people attempted to dim this light from Native people through the erasure of Native history and violent assimilation in boarding schools. For many schools implementing a tribal curriculum is new.

For many Northwest Native people, these time-honored teachings center on our connection to the river and the resources. Teaching about 7 species of fish in the Nch’i Wāna and their importance to tribal identity is a powerful lesson for the present and future generations