In 1836, Missionary Narcissa Whitman was relieved to see the flourishing garden at Fort Walla Walla (Hudson’s Bay Company). After several days of rest, the party of four American missionaries, Marcus and Narcissa Whitman, Henry and Eliza Spalding, continued down river several hundred miles to Fort Vancouver. At the Fort, Narcissa extolled the virtues of the garden in her journal. It was written in early September 1836 soon after their arrival at the “civilized” Fort Vancouver. [1]

Narcissa was particularly delighted with the apples and grapes:

“feasting on them finely. …I save all the seeds of those I eat for planting & of apples also. This is a rule of Vancouver. I have got collected before me an assortment of garden seeds which I take up [to the new mission at Wailatpu], also I intend taking some young sprouts of apple peach & grapes & some strawberry vines &C from the nursery here. Thus we have everything we could wish for supplied us ….”[2]

Eliza Spalding and Narcissa Whitman were the first American white women to cross the Oregon Trail. Due to their gender, they helped open a floodgate of American immigrants to the West Coast that proved to be an unwelcome onslaught of permanent settlers scattered among Indian tribes. As they settled into their frontier lives both women became well acquainted with Catherine Pambrun, the Cree wife of the Chief Trader at Fort Walla Walla.

The Spaldings settled at Lapwai (Idaho) near the future shared border of Idaho and Washington states. Ministering among the Nez Perce, the Presbyterian Reverend Henry Spalding was equally captivated by developing agricultural crops and introducing irrigation to the vast prairies of the Nez Perce lands. Highly accomplished as horse breeders and ranchers long before the arrival of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, the Nez Perce cultivated grazing lands for their stock in the verdant canyons of northeastern Oregon, southeastern Washington and all of north central Idaho. The canyons formed natural corrals protecting the herds from invaders and predators, and moderate winter temperatures encouraged lush feed.

Chiefs Red Wolf (Hemene Ilppilp) and Timothy (Ta-Moots-Tsoo) were the leaders of the Alpowai Nez Perce band (Asotin County, WA) that lived close to Lapwai and the Spalding Mission. Chief Timothy became a Christian convert and also followed Spalding’s agricultural advice to plant an apple orchard near his village. Using seeds and saplings in 1837 likely started at Fort Vancouver or Fort Walla Walla where Chief Trader Pierre Pambrun lived, a marvelous orchard sprang up. Like the one at Fort Vancouver, it was carefully tended by native people who enjoyed the sweet taste of their labors and welcomed the opportunity to develop a cash crop. In 1841, the exploring party of Charles Wilkes, led by Robert Johnson to the inland country was much impressed with the apple orchards already growing on Nez Perce lands.

Chief Timothy was noted as one of the four chiefs who were unfairly persuaded by Congressional politicians to sign away the Wallowa lands belonging to Chief Joseph’s band – the foundation of the Nez Perce War of 1877. Twenty-three years after the War, Indian scouts who had served under General O.O. Howard petitioned Congress for payment of wages earned in 1877. A few made other claims, too, like Luke Billy (Pa ka yat we kin), duly sworn January 20, 1900, at fifty years of age.

“…Where were you living when the Nez Perce war broke out? I was living on Salmon River. Were you a scout during the Nez Perce war? Yes.”

“… The Indian agent and General Howard said that we would be paid wages and any loss of horses or other losses. When General Howard wanted to cross Salmon River he tore down my house and took the logs to make a raft with which to cross the river with; after that white men took my place and kept it.

“Did you ever get any pay as a scout? No, sir. Did you ever ask for it? Yes; I asked for it. Did you furnish your own horse? Yes.”

“… I lost a lot of apples and fruit trees with my place after the house was torn down; I lost a lot of cattle and horses during the war—about 400 head all told.” [3]

The Third Productive Orchard

A lack of adequate irrigation and financial resources in the Yakima Valley delayed the efforts of the Yakama Indian Nation to establish apple orchards for more than twenty years. [4] Substantial apple and fruit orchards were planted at Fort Simcoe after it was ceded to the Yakama Indian Agency in 1859.

The following story was recollected by Judge E.V.Kuykendall. He was born in 1870, and raised at Pomeroy, WA on the Nez Perce Trail. Please note that the Yakama Indian Agency was removed to Toppenish, WA, in April 1922 without consulting the Yakama tribal council and over their subsequently loud protests. The move was enforced by the Bureau of Indian Affairs to appease white businessmen who lived inconveniently thirty miles away. [5]

Kuykendall writes:

“The third planting of the apple trees (and I believe the first in the Yakima section), was at Fort Simcoe, then seat of the Yakima Indian reservation, established by the great council at Walla Walla in 1855. Fort Simcoe was first established as a military fort in 1856, having a parade ground 200 feet square with buildings on all four sides. It was abandoned as a military establishment in 1859, and soon thereafter turned over to the Department of Indian Affairs. I do not know the exact date the apple orchard was planted in this parade ground, but it must have been between 1860 and 1864. [6]

My father was appointed as government physician at Fort Simcoe, and we moved there when I was only two years old, in 1872. As far back as I can remember one large tree [grew] about the middle of the west side near a pump, with large, fine cooking apples, and I was often sent by my mother to gather “pump” apples as we called them from the tree. My guess would be that this orchard was ten or more years old at the time I was old enough to remember. In my opinion, it was planted not later than 1864. In 1948 when I was there last, there were only two or three trees left as I recall. We left there in 1882, when the whole Yakima Valley was a sage brush desert. There may have been a few young apple trees in yards at Yakima City, where Union Gap now stands.” [7]

– Judge E.V. Kuykendall of Pomeroy, Washington

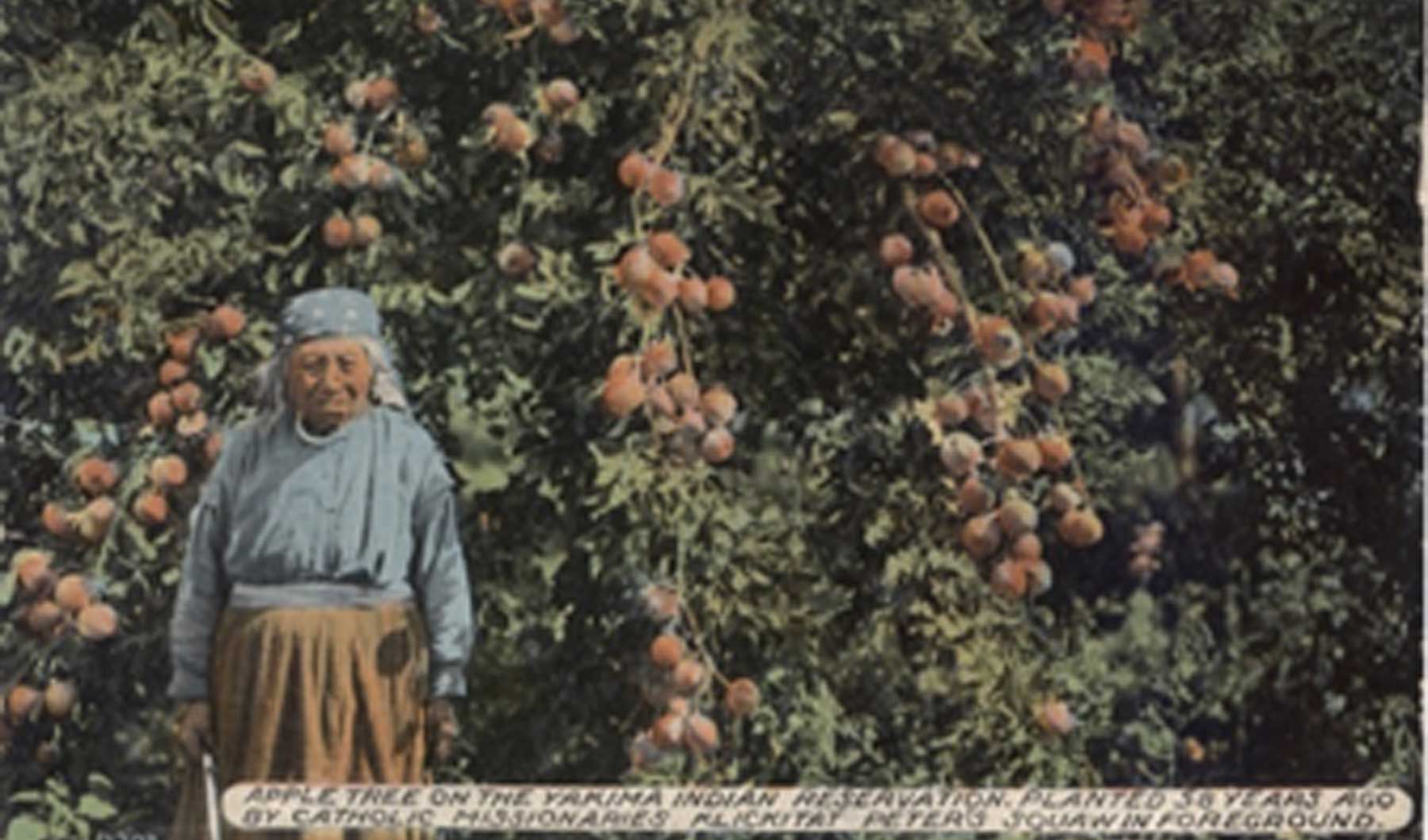

It is generally believed that the oldest commercial apple orchards in the Yakima Valley were planted about 1875. Near Fort Simcoe, twenty-seven miles south of North Yakima, stands an orchard planted by an Indian, Klickitat Peter, in 1877, with the help of Catholic missionaries. This is probably the oldest apple planting in what was later destined to become one of the premier apple-growing regions of the world.

Collecting the stories that connect people to place is the mission of Confluence. Stories relate and broaden our scope of understanding and appreciation for all people who contribute to our well-being through environment, trade and a lively exchange of knowledge.

End Notes

[1] “… Here we find fruit of every description. Apples peaches grapes. Pear plum & Fig trees in abundance. Cucumbers melons beans peas beats cabbage, taumatoes, & every kind of vegitable, to numerous to be mentioned. Every part is very neat & tastefully arranged fine walks, eich side lined with strawberry vines..” Whitman, Narcissa. My Journal 1836. Washington: Ye Galleon Press, 1994. 57.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Congressional Record, 1900.

[4] The tribal spelling of the Yakama Nation was formally changed in 1993, thus reflecting a closer pronunciation of their name. “Yakima” spellings continue to denote geographic locations. Old texts, journals and pre-1993 documents reflect the same spelling of “Yakima” for both.

Note: Kuykendall is referencing Yakama as the “third” site after the Fort Vancouver and Chief Timothy orchards described in the previous blog.

[5] An excellent article addressing this relocation to Toppenish is Talea Anderson, “I Want my Agency Moved Back, … My Dear White Sisters,” Pacific Northwest Quarterly 105 no. 2, Spring 2013. http://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1016&context=libraryfac

[6] The spelling of “Yakama” Nation was officially changed in 1993 to more closely reflect the tribal pronunciation of their name. The earlier spelling, “Yakima,” remains for geographic locations. In historical quotations the spelling has not been altered.

[7] Overley, Fred L. History and Development of Apple in Washington. 1921.