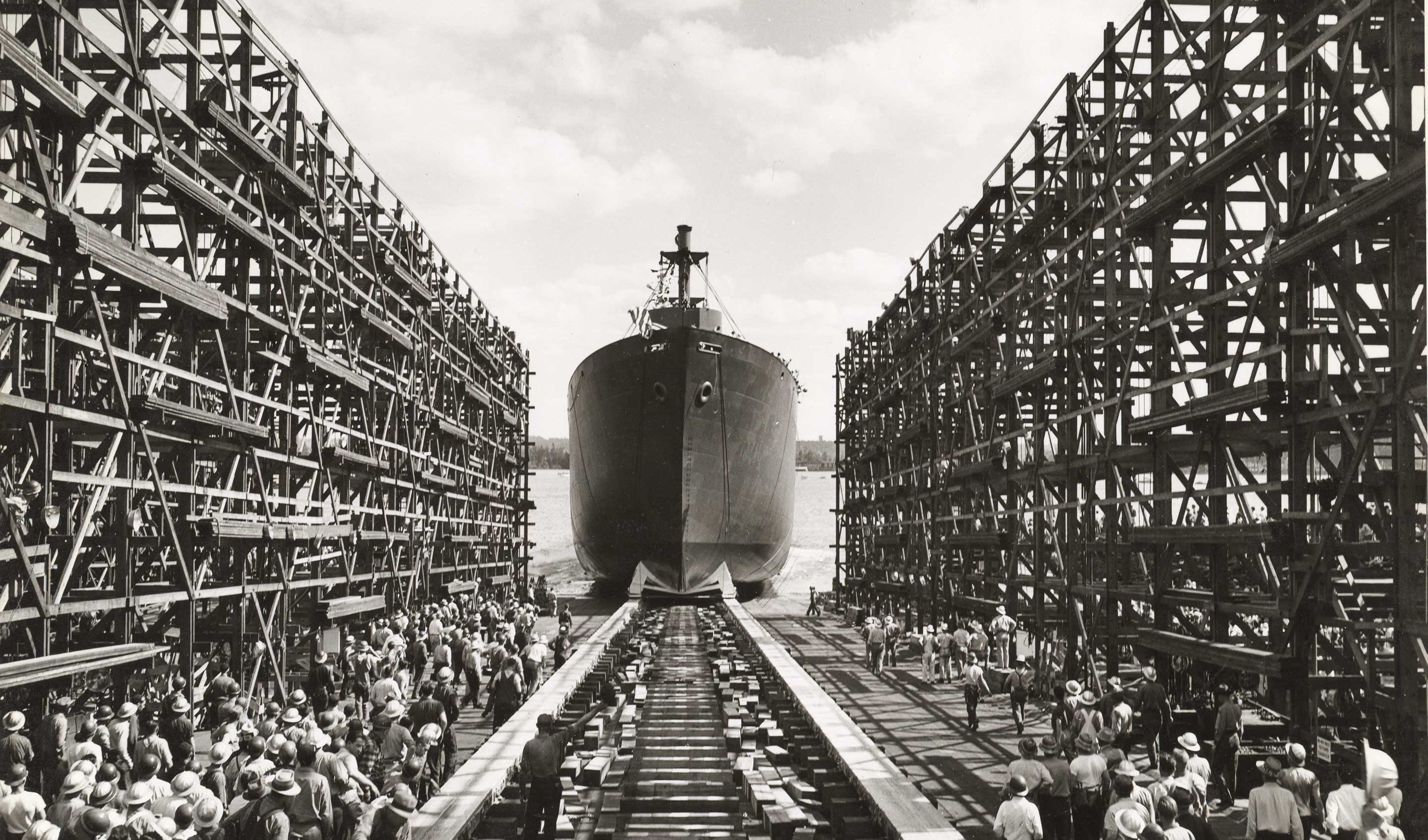

Industrialization arrived in full force on the Columbia River in World War II and with it American cultures changed in surprising ways. Pearl Harbor was bombed by the Japanese December 7, 1941 and less than one month later – late January 1942 – Edgar Kaiser announced the new construction of a naval shipyard on Vancouver, Washington’s waterfront at Ryan Point.[1] By April 1942 – less than three months after publicly announcing the new yard – the first naval vessel was launched. It would be one of a total of 141 aircraft carriers, Liberty ships, LSTs (landing ship, tanks) and transport and cargo ships.[2] Two other Kaiser yards were already in full production in Portland — Oregon Shipbuilding at St. John’s and the Swan Island Yard. Kaiser built those yards in 1940 to fulfill a contract with the British government for construction of 31 cargo ships to aid their war effort. With plenty of inexpensive electricity for lights and gear, the shipyards operated 24 hours a day.

The hydro-electric power generated by Bonneville Dam was a constant source of energy for the booming shipyards on the Columbia and Willamette Rivers. In fact, that was the Kaiser family’s connection to the Northwest. Henry Kaiser built Bonneville and Grand Coulee dams on the Columbia River from 1933-1940. His health care insurance programs were first developed for the workers on these dams. General George C. Marshall’s wife Katharine remarked in her memoir Together: Annals of an Army Wife (New York: Tupper and Love, 1946) that the Kaiser family and President Franklin D. Roosevelt were occasional guests in their beautiful home on Officers’ Row at Vancouver Barracks.

As young men and women enlisted for military service by the thousands, Kaiser began recruiting workers for the new yards. There was a severe shortage of skilled industrial workers in the region: in 1940 only one-sixth of the 318,000 people in the Portland/Vancouver area were employed in industry. By 1940, over 140,000 people were employed in the Kaiser shipyards, and many others worked in industries connected to the yards.[3] Workers were recruited nationwide and the surge of newcomers impacted housing, schools, medical services, and the flow of basic supplies. And yet, Kaiser needed even more skilled laborers and so, they turned to women.

“Proper” jobs for women in the area ranged from $20/month (with room & board) to $70/month for experienced office work. Skilled workers who had completed a short training course in welding earned $230/month in the shipyards. Electricians earned even more once they completed readily available courses but the majority of women seemed content to be welders. Reflecting on those war years, in an interview with Amy Kesselman in 1998, shipyard worker Ruth Drury commented, “… we just accepted what was handed to us and didn’t think anything about it.”[4]

By 1943, more than 27 percent of the Kaiser yard workers were women – the highest percentage of female industrial workers in the nation throughout the war production years.[5]

Yakama tribal member Virginia Beavert enlisted in the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) early in World War II but took a discharge when it was transformed in 1943 into the Women’s Army Corps, as the regular army. She met her uncle and his wife in Portland as she was returning to her home on the reservation. “…on my way home I happened to run into my uncle and he said he married my best girlfriend. And he said, ‘Oh, well, we’re working at Vanport, we’re welding. You want to come home with us and have dinner?’ Well I went home with him and they talked me into staying. And he said, ‘You can take a welding school and start welding. You don’t have to go home, do you?’ I said, ‘well, I was on my way home but I don’t know what I’d do if I got there.’ So I enrolled in welding school. I picked it up real fast. Of course, they were talking welding all the time. He was a supervisor and she was one of the top welders. So with that I learned it real fast. I got on a troubleshooting crew. People make mistakes; we’d go and correct them. We were working on those big ships that hauled all the food and everything to the battlefields and we started welding submarines. That was a promotion so I was really making a lot of money. Well, we were doing real well and something happened in Europe that made all these guys angry that were on my team and they all joined the army, so I did too.” Ms. Beavert joined the WAC’s and served as a radio operator for B-29’s. Later she served at Hanford, WA, with a top secret classification. [6]

Children were greatly affected as women went to work and families struggled to adjust. Often, both parents worked at the same yard but on different shifts. Schools ran double shifts, too, and teachers often went to their students’ homes to check on them if they missed school or were ill. There was grave concern for epidemics of children’s diseases due to the extraordinary convergence of newcomers into small communities. Families who were new to the region were sometimes unfamiliar with food, weather and entertainment in the area. Written directions or instructions were posted. Prefabricated homes sprang up in newly-created housing districts but people did not know their neighbors. In Vancouver, there were stories about the new houses replete with electric lights and stoves. Some of the newcomers were unfamiliar with those amenities and tried to build a wood fire in the electric stove. Local people were highly suspicious of those “big city New Yorkers” invading their small town, but less than three percent came from north Atlantic states. Forty-seven percent of all newcomers came from the Pacific Northwest and California.[7]

Almost overnight Vancouver became a “boom town.” More than 50,000 people moved to the former community of 18,000 people and hungry shoppers descended on downtown Vancouver. Providing accessible shopping and increased availability of goods led to two Pietro Belluschi-designed shopping centers. Architect Belluschi was awarded recognition by the New York Museum of Modern Art as a model for future retail shopping establishments.[8]

Henry Kaiser was one of the first to introduce company-supported child care centers and several of these opened in Portland at or near the shipyards. In Vancouver, Kaiser felt the Vancouver School District was doing a splendid job of creating neighborhood centers for day and evening care. The demand for qualified teachers also grew and Washington had to overlook their state law requiring female elementary school teachers to be unmarried or widowed. The shortage was too strong and in hindsight, became seen as a ridiculous law.

Racial tensions were not uncommon. The greatest number of African American employees was hired at the Vancouver shipyard – a community practically void of intermingled races before World War II.[10] The crews were integrated in the yard and in the new neighborhoods but integrated entertainment like dances and movie theaters raised tensions for some. Adjustments were made and often smoothed over by the common cause of the “war effort,” but among the female workers in the yards, the crews were technically divided by experience and skill. Invariably, black women were “helpers” or “laborers.” Often, black women were barred from skilled work regardless of qualifications and training.[11]

More than 40,000 Native Americans left reservations to work in the defense industries of the nation. The Oregon History Project writes, “In Oregon, the Chemawa Indian School near Salem sent about forty students to a training facility in Eugene run by the National Youth Administration (NYA)—a program established by the Works Progress Administration during the Depression to help put young people to work. In 1942, the NYA was transferred to the War Manpower Commission, and training facilities began to focus on skills such as welding and electrical to prepare students for shipyard work. Most of the trainees in the Eugene facility went on to work for the Kaiser Shipyards in Portland and Vancouver.”[11] The BIA supported and encouraged Native American women joining the mainstream workforce because in large part it reflected their programs of “cultural assimilation.”[12]

The S.S. Pendleton was the 49th “T2” model tanker built at the Kaiser Swan Island shipyard on the Willamette River in Portland. T2s were the largest “navy oilers” of their time, just over 500 feet in length and displacing 21,100 tons when fully laden. Their holds could carry nearly 6 million gallons of oil or gasoline. The ship was named for the Oregon town of Pendleton and tribal members, some of whom worked at the Swan Island yard, were invited to its launch and dedication.[13]

The gifts and dynamics of the Columbia River were changed by the war industry. The image of the river was transformed into a powerful resource to support industry rather than a living resource for human culture and everyday life.

End Notes

[1] Edgar was Henry Kaiser’s son. He built a home in Vancouver and oversaw all of the Kaiser Shipyard operations, medical and childcare services in the Portland/Vancouver region.

[2] Marker at the Kaiser Shipyard Memorial, Vancouver waterfront.

[3] Kesselman, Amy. Fleeting Opportunities. New York: State University of New York Press, 1990. 14.

[iv] Ibid. 9.

[5] Ibid. 29.

[6] Beavert, Virginia. Interview with Confluence. September 2016.

[7] Vancouver Housing Authority. 50 Years of Progress. Vancouver: Vancouver Housing Authority, 1992. https://vhausa.org/about-vha/our-history

[8] Ibid.

[9] Kesselman. Fleeting Opportunities. 41.

Note: When the first Euro-Americans began to build trading posts along the Columbia River they frequently intermarried with indigenous people, but after the Indian treaties of 1855, interracial marriages were discouraged except on the reservations.

[10] Ibid. “While women composed 31% of the black work force [at Vancouver] in 1943, they composed only 20% of black welders, 21% of black electricians and a tiny percent of the other skilled trades.”

[11] Platt, E.A. “Native American women from Chemawa train to work in shipyards.” The Oregon History Project. March 17, 2018. https://oregonhistoryproject.org/articles/nine-native-american-women-from-chemawa-train-to-work-in-shipyards/#.WLSmNm8rKM8

[12] Ibid.

[13] Kaiser Permanente. “Our History.” Kaiser Permanente. http://kaiserpermanentehistory.org/our-story/our-history