Indigenous people often speak of the memorable “sound” of Celilo Falls. Celilo was the most powerful series of rapids on the lower Columbia River, but Kettle Falls was the largest and most formidable on the entire Columbia River System. Angus McDonald, retired Chief Trader at Fort Colvile referred to Kettle Falls as “Colvile Falls” and wrote in 1872, also known as “Kettle Falls”:

“When the Columbia is up in June, the sound of the Colvile Falls[1] on a silent summer night is very grand. All the congregated water from Ross Hole to the smallest spring of Condi River are massed in that torrent. Its Indian name is Schonet Koo, meaning ‘Sounding Water’. Salmon as heavy as one hundred pounds have been caught in those falls….”

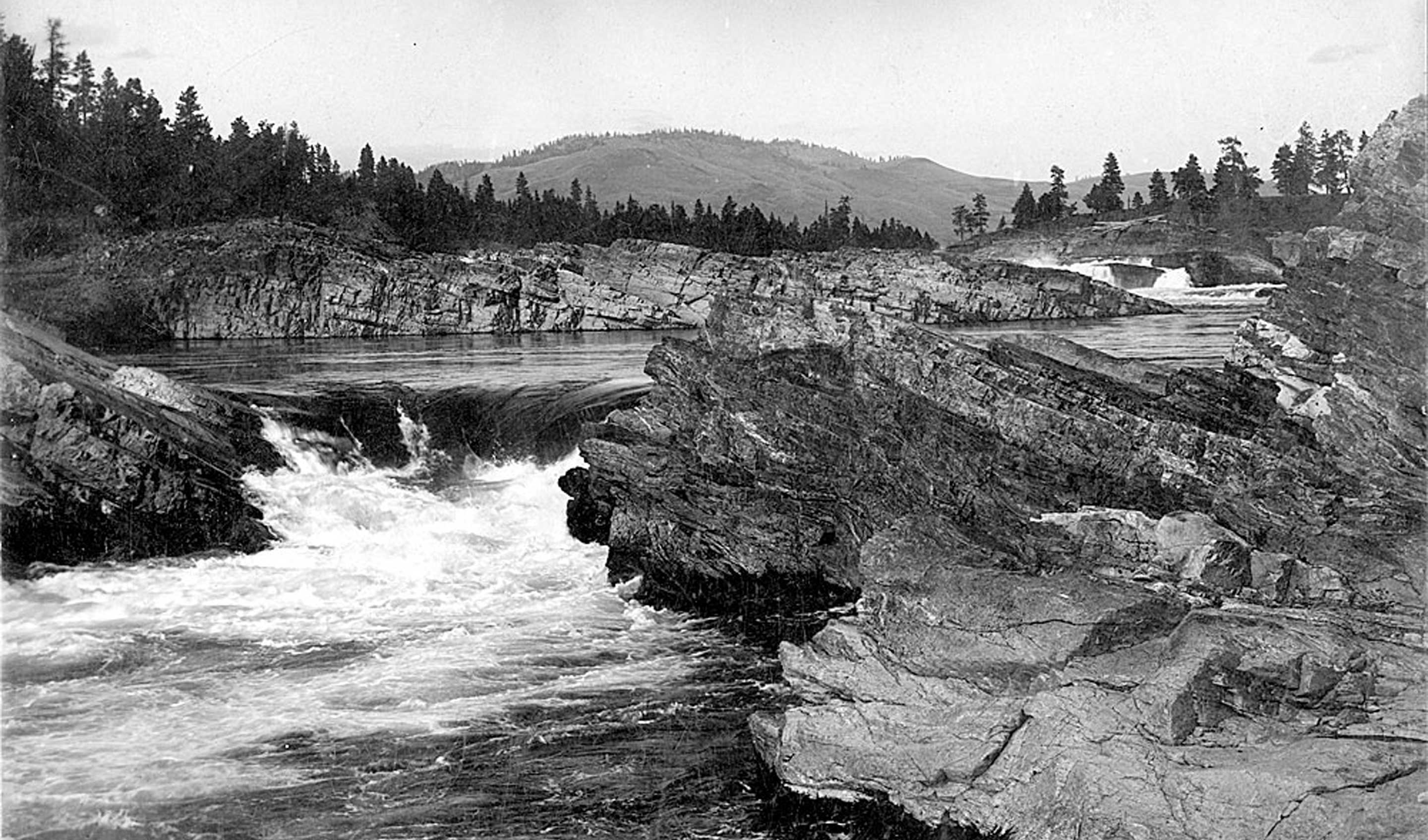

Lt. Symons recorded in his official report in 1881: “They are the most complete and total obstruction to navigation met with on the Columbia, the perpendicular fall being about twenty-five feet at low water, divided into the upper fall of fifteen feet, and the lower one of ten feet, the two falls being within a few rods of each other.”[2]

No one chose to navigate Kettle Falls, including David Thompson who described coming upon them in 1811 on his first voyage down the Columbia River with five experienced Canadian voyageurs and two Iroquois canoe men, all of the North West Company. Thompson wrote that the native people had assembled for the First Salmon Ceremony, gathering from around the region on June 19, 1811: “For the next few days, only one man, with a spear, worked the rocks of the falls, although many salmon were passing. Then after the salmon chief announced that the required number of salmon had passed, more men, using nets and baskets, began the major harvest.” Thompson named the falls, and the inhabitants, “‘Ilth koy ape” after these large woven baskets, using a local phrase that meant kettle trap or net.[3]

The tribes who gathered at the Falls included the Colville, the Spokane and the “Sinixt”[4] from the Arrow Lakes region of the Columbia. Sinixt means “Place of the Bull Trout” (Salvelinus confluentus) a common fish of the upper reaches of the Columbia River. Today, the Sinixt live primarily on the Colville Indian Reservation in Washington, where they form part of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation and are recognized by the United States government as Many Sinixt continue to live in their traditional territory on the northern side of the 49th Parallel, particularly in the Slocan Valley and scattered among neighboring tribes throughout British Columbia, however the Canadian Government declared the Sinixt legally extinct in 1956.[5]

The widely-acclaimed artist of the fur trade era Paul Kane was enamored with Kettle Falls and the native people who lived and gathered there. In 1848, Kane wrote, “On the 17th of September I returned again to [Fort] Colvile.[6] The Indian village is situated about two miles below the fort, on a rocky eminence overlooking the Kettle Falls. These are the highest in the Columbia River. They are about one thousand yards across, and eighteen feet high. The immense body of water tumbling amongst the broken rocks renders them exceedingly picturesque and grand. The Indians have no particular name for them, giving them the general name of Tumtum, which is applied to all falls of water. The voyageurs call them the “Chaudiére,” or “Kettle Falls,” from the numerous round holes worn in the solid rocks by loose boulders. These boulders, being caught in the inequalities of rocks below the falls, are constantly driven round by the tremendous force of the current, and wear out holes as perfectly round and smooth as in the inner surface of a cast-iron kettle. The village has a population of about five hundred souls, called, in their own language, Chualpays. They differ but little from the Walla-Wallas. The lodges areformed of mats of rushes stretched on poles. A flooring is made of sticks, raised three or four feet from the ground, leaving the space beneath it entirely open, and forming a cool, airy, and shady place, in which to hang their salmon to dry.”[7]

Many of the voyageurs headed up river in the autumn were relieved to reach Fort Colvile near Kettle Falls and the beautiful pine forests of the region. Fur trader Angus McDonald recalled that the H.B. Company made all of the Columbian boats at the Fort of native Yellow Pine. For stamina and fortitude, “some excellent beer and some superior whiskey were distilled and furnished for the Mess, but the laboring men fared on very simple rations; if simple, they were solid, however, such as flour, salmon, lard or tallow, venison and potatoes; no sugar or coffee or tea until later days; regular rations of such were issued. McDonald also insisted that the Colvile Falls were the only ones of the Columbia River “never run by us. Although their elevation is only about 20 perpendicular feet, no state of the water changes the pitch of the torrent, and the compact momentum is always so strong that the Company never ran it; and if they did not, it is certain that others did not try it.”[8]

McDonald described the fishery, “Salmon are taken at those falls by basket and spear…. As the eager fish glances to the surface of the whirlpool, looking to his leap, he is pierced and dragged quivering ashore. Now and then, however, the spear man loses his life…. Having speared a strong fish, the sudden struggle and iron pressure of the mighty waters jerked these poor fellows from the dizzy standing, and falling headlong into those terrible whirlpools they never breathed again.”[9]

His excellent description continued with more details: “The basket is a vessel made of stout hazel or birchen osiers hung to the lower edge of the Falls by a rope of the same boughs. The fish that fail in their leap are cast back and fall by scores into the ever open basket. When it is full, two strong, hardy men strip, and club in hand go down through the drenching cold foam into the basket to knock the yet living in the head and heave them up or hand them up with the already dead. One basket has caught a thousand salmon in a day in this way. About fifteen minutes of that shivering spray is all they can stand and then a new relay of fresh men take their places. These splendid fish are so thickly crowded in the billows at the foot of the falls that I often thought they could be shot. This, however, the Indians would not allow. Probably the salmon is the cleanest and shyest of all fish. But the many fisheries now on the lower Columbia established to can and export them are fast at work in destroying the noble supply, for they are no sooner above the Columbia bar than they are waylaid by numberless nets and their way to the spawning ground counter-marched by death. Wherefore, if not otherwise provided for, the extinction of the Columbia River salmon is only a question of time. A cloudless sky at eight o’clock in the morning and four in the evening are the best hours to see the salmon’s ascent against the falls of his native rivers.”[10]

Father Pierre Jean DeSmet watched men catching up to three thousand salmon each day, using spears and J-shaped baskets placed in the falls. After cleaning and filleting the catch, the women hung the fish to dry in the sheds. Excess fish were used later for trading.[11]

As early as 1882 when Lieutenant Symons and Alfred Downing officially surveyed the Upper Columbia for the US Government, the men recommended that a channel could be cut and a lock placed in it, the material taken from the channel being placed in the interval between the island and projecting point, forming thus a continuous channel for a canal from the quiet waters above to the quiet waters below the falls. But Grand Rapids, another serious obstruction to navigation, was only about seven miles below Kettle Falls, and no scheme for giving navigation around Kettle Falls would ever be entertained which did not contemplate also giving it around Grand Rapids.[13]

Congress showed very little interest in such a scheme for another fifty years, but by then, they planned to build a dam for hydroelectric energy and irrigation.

Grand Coulee Dam “Reclamation – Managing Water in the West”[13]

The proposal to build the Grand Coulee, a gravity dam, was the focus of a bitter debate during the 1920s between two groups. One group wanted to irrigate the ancient Grand Coulee with a gravity canal, and the other supported a high dam and pumping scheme. Dam supporters won in 1933, but for fiscal reasons the initial design was for a “low dam” 290 feet (88 m) tall which would generate electricity, but not support irrigation. The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation and a consortium of three companies called MWAK (Mason-Walsh-Atkinson Kier Company) began construction that year.

After visiting the construction site in August 1934, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt began endorsing the “high dam” design which, at 550 ft. (168 m) high, would provide enough electricity to pump water to irrigate the Columbia Basin. The high dam was approved by Congress in 1935 and completed seven years later. On June 1, 1942, the first water over-topped its spillway — consigning to the deep waters of Lake Roosevelt the famous Kettle Falls. Over ten thousand years of indigenous fisheries, traditions and lifestyles fell beneath the choppy white caps of the lake.[14] Vanquished with the falls and rapids was the ancient roar of “Sounding Water” likely never to be heard again in our lifetime.

[1] Angus McDonald claimed that the correct spelling of “Colvile” had a single “l” in the last syllable to match the spelling of Hudson’s Bay Company General Andrew Colvile, deputy governor, 1839-1852; governor, 1852-1856.

[2] Symons, Thomas William. The Symons report on the upper Columbia River & the great plain of the Columbia. Fairfield, WA: Ye Galleon Press, 1967. 33.

[3] Oldham, Kit. “David Thompson party reaches Kettle Falls on the Columbia River.” HistoryLink. 2003. http://www.historylink.org/File/5102

[4] Wonders, Karen. “Sinixt.” First Nations. 2008. http://www.firstnations.de/invasion/sinixt.htm

[5] Ibid.

[6] There were two Fort Colvilles but the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) fort was spelled without the double “l” – see above. The trade center Fort Colvile was built by HBC at Kettle Falls on the Columbia River in 1825 and operated in the Columbia fur district of the company. The fort was a few miles west of the present site of Colville, WA. It was an important stop on the York Factory Express trade route to London via the Hudson Bay. The HBC for some time considered Fort Colvile second in importance only to Fort Vancouver until the founding of Fort Victoria.

Fort Colville was a U. S. Army post in the Washington Territory located 3 miles north of current Colville, WA. During its existence from 1859-1882, it was called “Harney’s Depot” and “Colville Depot” during the first two years, and finally “Fort Colville”. Brigadier General William S. Harney, commander of the Department of Oregon headquartered at Vancouver, WT, opened up the district north of the Snake River to settlers in 1858 and ordered Brevet Major Pinkney Lugenbeel to establish a military post to restrain the Indians lately hostile to the U. S. Army’s Northwest Division and to protect miners who flooded into the area after the first reports of gold in the area appeared in Western Washington newspapers in July 1855.

[7] Ruby, Robert and John A. Brown. The Spokane Indians: Children of the Sun. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1970.

[8] Angus McDonald, born in 1816 at Craig House on Loch Torridon, Scotland, emigrated to North America in 1838 to serve with his uncle Dr. Archibald McDonald at the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Fort Colvile. Angus served at various Company posts, including Fort Nisqually until he succeeded his uncle in 1852 at Fort Colvile as Chief Trader. He remained there until 1872. In 1840, McDonald married Catherine, sister of the Nez Perce chief Eagle of the Light and they raised 13 children in the Pacific Northwest.

See Howay, F.W., William S. Lewis, and Jacob A. Meyers. “Angus McDonald: A Few Items of the West.” Washington Historical Quarterly 8, no 3 (July 1917). http://journals.lib.washington.edu/index.php/WHQ/article/view/9115

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Lake Roosevelt Administrative History. “When Rivers Ran Free.” April 22, 2003. https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/laro/adhi/adhi1.htm

[12] Symons. The Symons report on the upper Columbia River & the great plain of the Columbia. 23

[13] Northwest Region. “History.” Reclamation Managing Water in the West. https://www.usbr.gov/pn/grandcoulee/history/index.html

[14] Federal compensation to the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Indian Reservation and the Spokane Tribe for the loss of the lands, falls and rapids due to construction of Grand Coulee Dam remains in dispute. See also:

Spokane Tribal Business Council. “Grand Coulee Dam.” Spokane Tribe of Indians. http://www.spokanetribe.com/grand-coulee-dam

Hotakainen, Rob. “Tribe hopeful its long wait for dam payment will end.” McClatchy DC Bureau. September 30, 2013. http://www.mcclatchydc.com/news/nation-world/national/article24756043.html

Sprague, Holly. “Unjust Compensation: Grand Coulee Dam, Indian Claims, and the Colville.” Thesis. Massachusetts: University of Massachusetts, 2011. http://scholarworks.umass.edu/chc_theses/11/.